At the start of 2025, my grandma passed away, my last remaining grandparent. With the sadness and clearing out her house also came the slow realization that an access had been lost to knowledge and stories of the past; a little part of the world was now closed off. When I saw Murmuring Matter by Zoë Sluijs, I immediately had to think of my grandparents. I thought of the field where the ashes of my father’s parents were scattered and of the grave where my mother’s parents are buried.

The multidisciplinary project is an exploration of listening; to each other, but mostly to the non-human. How do we flow over into nature? Does the ground absorb the stories of our grandparents, and how could we hear that? This search for ways of connecting with the non-human and the invitation to open your mind (and ears), is an important theme in Sluijs’ work. How can we use our imagination to become closer to the physical world around us?

In your artistic practice, you use storytelling (in different forms) to explore the many connections between living (and potentially living) organisms. How did your bond with nature form? And do you experience this bond differently now than when you started as an artist?

It’s hard to relate with ‘nature’, a concept with a (somewhat unclear) definition that in itself seems to present a separation between man and nature. I’m convinced that we all more or less have a bond with ‘nature’, because we belong to it ourselves. And exactly like you say: the different relationships between living entities, they fascinate me.

What being an artist has offered me is the freedom to ask questions about these relationships that don’t necessarily need to be answered. And the approach to asking those questions doesn’t necessarily need to be placed within rational thought. The freedom to speculate and to fantasize means I can keep rediscovering and deepening my relationship with others.

What exactly fascinates you so much about those relationships between living entities.

It’s in those relationships that we can learn more about ourselves. Because it’s more accessible to see how, for instance, a plant cannot be separated from the soil that it gets its water/nutrition from, and cannot be separated from the air where oxygen and carbon are exchanged. That porousness of the body, where the one flows over into the other, is no different for us as humans. And yet, separating (and determining a hierarchy between) organisms is deeply rooted in Western thought. In this research, I keep discovering again and again how my own worldviews are shaped by this. Sometimes, that’s pretty confronting. That’s why I see it as an important challenge not to view myself as an individual, but to see how what I eat, what I breathe, the water that flows through my body, connects me inextricably to the rest of the world.

Why is storytelling such a powerful tool to explore and strengthen such connections?

The way in which we understand our surroundings is held together by stories. It’s a method we’ve used since the dawn of humanity to explain our environment. Therefore, the ways in which we relate to others (human or not) are linked to the stories we take in. These relationships are dependent on how we understand the other. The story as a medium also presents the possibility to experience a situation from the perspective of someone else. This form of empathy is crucial to discover a relationship with another in a healthy way. And it gives room for speculation and the radical reshaping of our perspective or everyday environment.

On your website, the first thing you see is the quote “If the rock and the plant that seem not to say much are in fact living story creators, then maybe it is a matter of learning a new language.” Where does this quote come from?

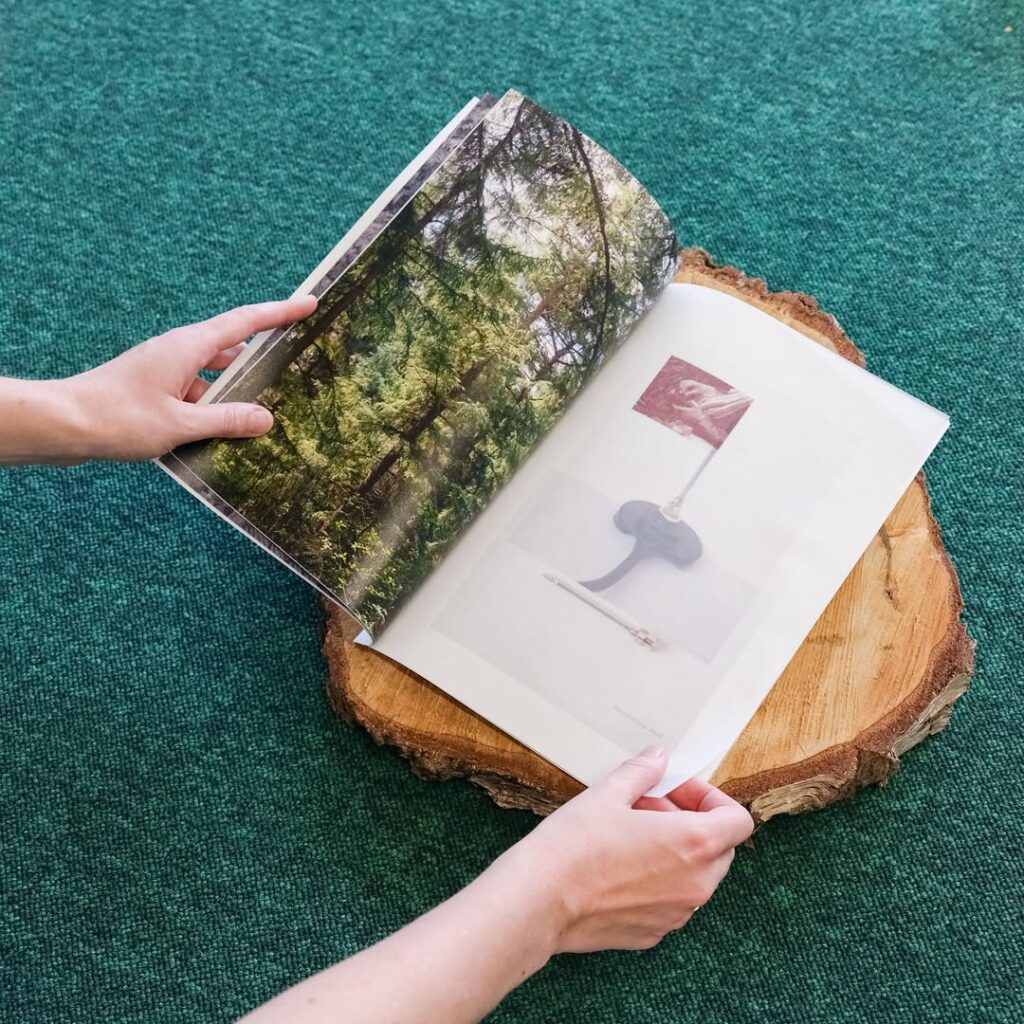

That’s a quote from a piece of text I once wrote for a performance in the Academiegalerie in Utrecht. During the performance, I wrote the text on an overhead projector, which projected it on the wall. Then I gave a short recital. This was the beginning of a unification with a larger research into language and the many ways of listening to that which, at first glance, seems not to speak. In 2019, I made a photography book in which a group of scientists goes looking for life in rocks. The desire to do something with that silence, or what we interpret as silence, is something that often comes back in my work.

You originally started as a photography student, but you then started focusing (with collective De Nieuwkomers for instance) on more multidisciplinary and exploratory art. Where did the desire to expand your practice in this way come from?

You’re right, until 2020 I mainly worked exclusively with photography. And setting up the art collective De Nieuwkomers certainly brought a breath of fresh air. Between 2020 and 2023, we squatted on a farm with a vegetable garden and chickens. Here, we invited artists for residencies and organized public events. In this period, my practice and my daily life became inseparable, and gardening, cooking, shaping these alternative living conditions, pretty much became part of my work. Although the collective is inactive at the moment, the impact it had on my artistic development can still be felt.

Could you tell a bit more about De Nieuwkomers? How did you find each other and what made you work together as an art collective?

We met during our bachelor’s degree in photography and film. We graduated in the year 2020, which was a difficult process because of all the disruptions at the start of the pandemic. That was a shame, but it also gave us the space to think about what we wanted to do as freshly graduated artists. We really wanted to move in together, and from our search for housing, many questions arose about ‘living together’. After we decided to squat in rural areas, we also had the time and space to attack these questions in a playful way.

It was also a reaction to making art within institutional environments. We were looking for a free way of making, within frameworks we could create ourselves. That’s how sharing a vegetable garden, cooking together and looking for a connection with our surroundings became part of our practice.

Murmuring Matter (in part) arose from the passing of your grandfather, and the imagination that his many stories now would keep flowing into the ground. As someone who lost his last grandparent at the start of the year, I find this image very touching and comforting. It feels very intuitive and almost self-evident, but I’d never thought of it that way. How did you find this idea?

My grandparents are buried at a remarkable location. Near to where they lived, there’s a natural burial ground. A small bit of forest is used as a resting place. You couldn’t really tell: there’s no stones or signs to indicate where people are buried. But you don’t need them. I still know exactly between which trees we laid my grandparents. From the path, I can look at the trees that grow around them. And for me, in this spot the separation between human and environment disappears. Here, my grandparents have become part of the forest. And I started wondering: if my grandpa’s body has become the forest, where do all the stories go that seemingly kept pouring out of him during his life?

He would write sometimes. For instance, he wrote a ‘pocket book of English’, in which he described how we form the sounds that become words with our lungs, vocal chords, tongue and lips. This inspired me to also think about how we could listen to stories once this corporeality no longer applies.

Looking at your work, I was reminded of a theory once presented to me: all art comes from a fear of death. I don’t agree with this statement – I find it very simplistic – but I am curious what you think about this. What would you say to this theory?

I’m not familiar with this theory. But my first reaction would be that, in this project, I didn’t act out of fear, but out of curiosity. Besides, for me this work is not about death. For me, it’s about language, about learning to listen and questioning the relationship to the non-human. You could even say that this work carries both life and death together. Makes them equal. Both as part of existence.

In works like The Possibility of Life and Consciousness Within Rock and Murmuring Matter, there’s an interesting tension between empirical science and alternative forms of knowledge. Why do you choose to approach your projects through such a scientific lens?

Because that scientific approach has such a big influence on my worldview, it’s interesting to treat it in a completely different way in my work; the language, the aesthetics and the tools used. As an artist, you get to use the equipment in a playful manner. This way, it questions the idea that we experience a clear reality with scientific tools. Just like a camera, a microphone makes a translation of what it records. A friction emerges between free interpretation, hard data, and a speculative approach.

For this project, you used a special microphone designed by artist Jez Riley French. How did you discover his work, and did you also look into other technologies or techniques for this project?

The work of Jez Riley French was recommended to me by a fellow student. In his work, I think I see the same playful approach to using scientific tools. He uses different techniques to create music and installations with his daughter. On top of that, he made the microphone that he created available for others.

I found a completely different technique for listening to environments through the work of Pauline Oliveros. She was a musician and composer who developed several listening techniques that she shared around the world. Her exercises are close to forms of meditation, and are used in listening sessions, but also performances with singing or experimental instrumental improvisation. Her work is about listening with your entire body. Again, this questions the boundaries between your own body and your surroundings. For instance through breathing exercises that direct your consciousness to the air that’s entering and leaving your body. Or even just by asking how far your hearing reaches, you are connected to your surroundings in a different way. At several moments, these techniques recurred in my research.

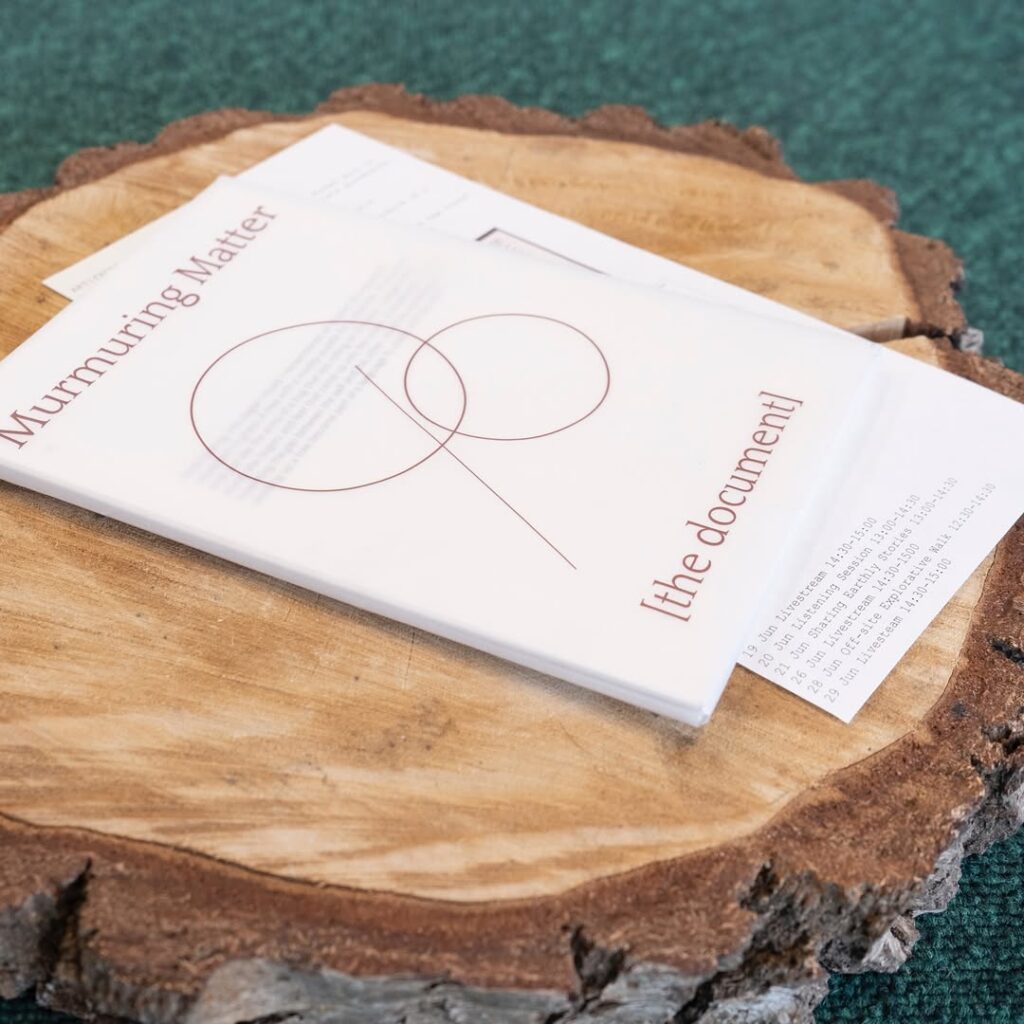

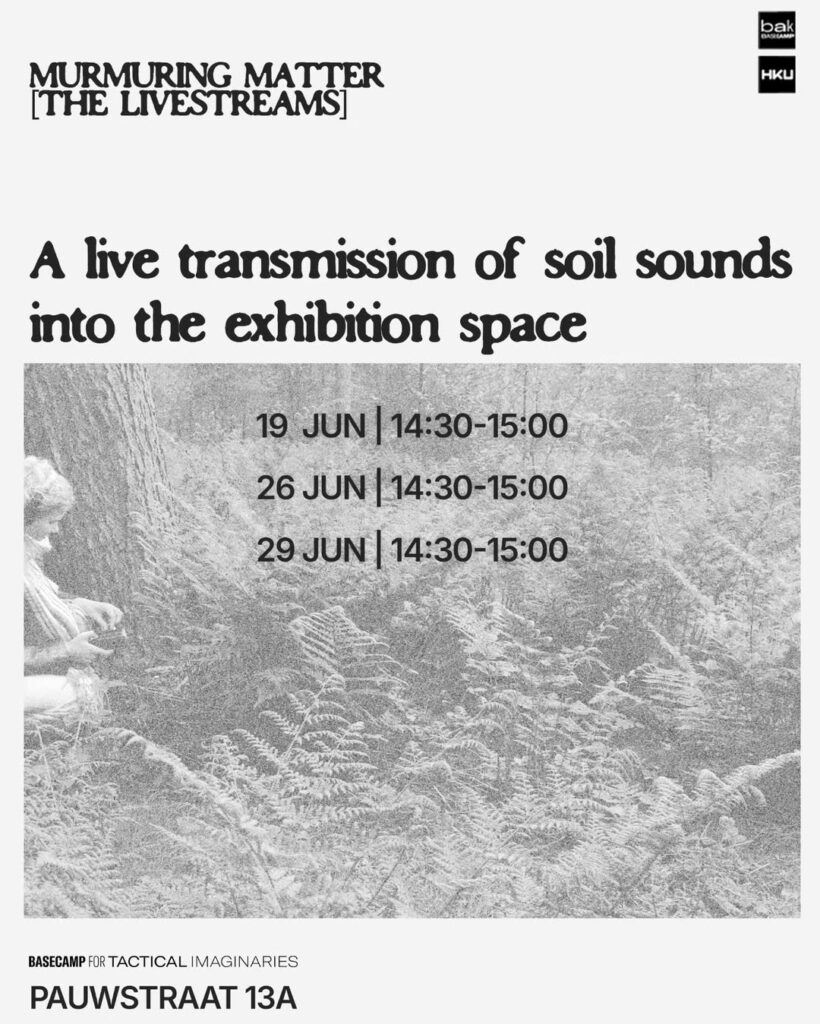

Murmuring Matter consists of a presentation of your research in the shape of an installation, but also of communal listening sessions, an evening of sharing stories and a walk through nature. What stuck with you the most from the communal activities?

To me, the events are a crucial part of the work. That’s where it comes to life, for example, in the conversations we held. It’s when others get the chance to become an active part of the research that beautiful things happen. There was a very intimate exploration of sound and our own voices during the listening session, we found a lot of shared recognition while sharing stories from all around the world, and during the walk we were captivated by the big lives of little frogs and we listened to an old chestnut tree with a contact microphone. It’s these special moments that arise in situations that I made space for, but that are shaped by the people participating.

It feels a bit lame to ask, but what do you hear when you listen to a chestnut tree?

That’s not a lame question at all. I think it’s the question. The question ‘what are we listening to now?’ always comes up when I use the contact microphone. For me, it’s often not about the answer, but about the speculation that follows the question. This is what we thought about while we were listening to the tree. Part of the tree consisted of dead wood, in which we could hear the movements of the many ants. It was teeming. That sounds like a series of little creaks and taps. Like it was being nibbled on. Later on, when the wind picked up, we also heard a young birch scratch against the branches of the chestnut. I find the sound of a squeaking and creaking tree in the wind fantastic. We also realized then that the sound of a waving birch resonated through the chestnut. That those two are involved with each others’ movements as neighbors.

More Zoë Sluijs: