Silvy Crespo is a French-Portuguese documentary photographer and writer. Since 2019, she has been working on a project about the communities affected by large-scale mining in Portugal. Its first instalment, ‘The Land of Elephants’, deals with the looming threat of lithium mining in northern Portugal. Second chapter ‘The Elephant’s Foot’ takes us to the Beiras region, where the damage of almost a century of uranium excavation can still be seen and felt, decades since the mines have closed. This long-term project shows the costs of extractivism and highlights the fight of local communities to stop the opening of new mines.

With her work, Crespo tugs at the carpet of Portuguese society, confronting issues that many would rather keep silent or hidden, that continue to grow as you’re looking away: the destructiveness of modern-day industrialization or the traumas of colonialism and war. These things bury themselves deep within the landscapes and the people they wound – polluting, corrupting, devastating – but remain conveniently concealed for those eager not to think about them (or profit from them).

At the end of 2024, you shared a sneak peek of ‘The Elephant’s Foot’, the follow-up chapter to ‘The Land of Elephants’. Obviously, there are no elephants in Portugal, so what do the elephants in these titles mean?

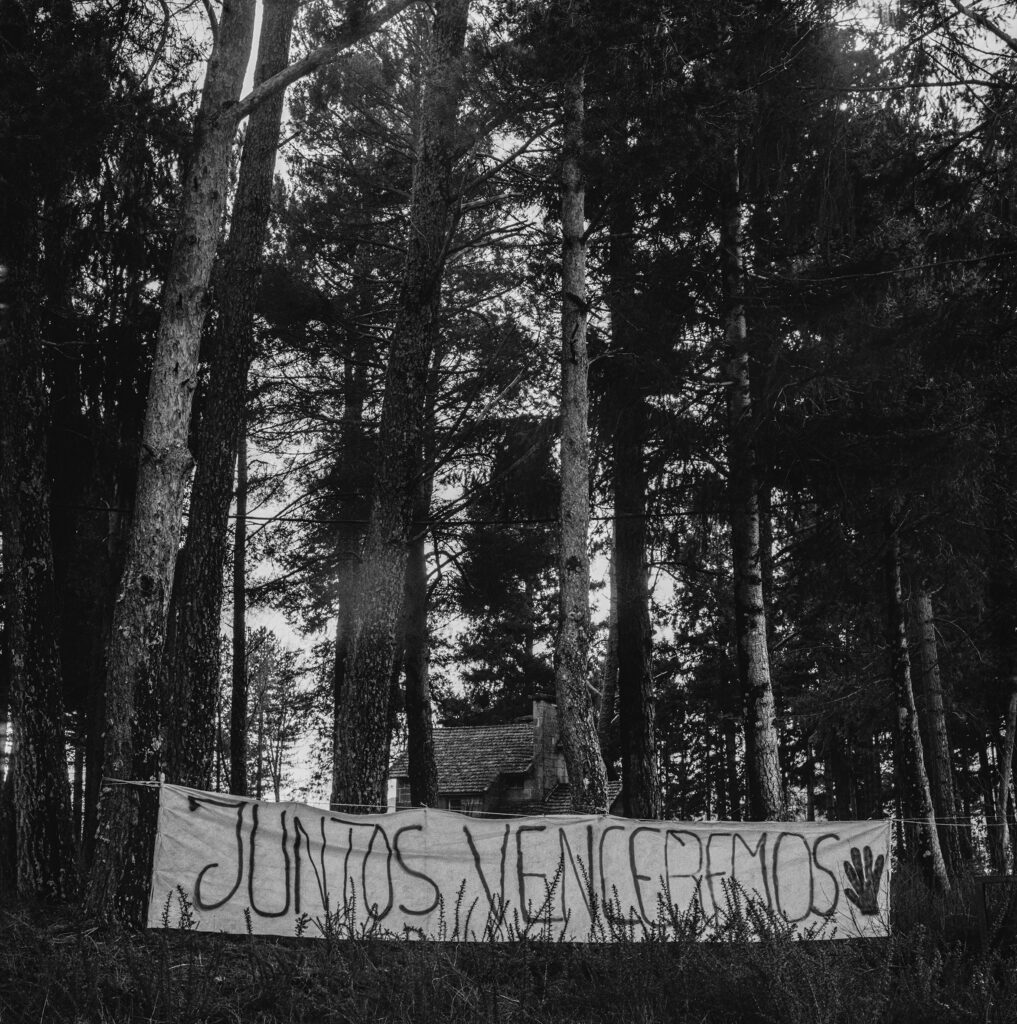

The ‘elephant’ in the mining industry jargon refers to large size deposits. The title ‘The Land of Elephants’ was inspired by a quote from Elisabeth Gaines, a Non-Executive Director and Global Ambassador of Fortescue Metals Group, who said, in a 2019 interview to the Financial Review, that: “Portugal is elephant country as well. We are still hunting for elephants in elephant country.” Gaines was referring to lithium hunting in Portugal, and more precisely, in the Barroso region. The Barroso region designates a territory in the northern mountains of Portugal, which extends from the municipality of Montalegre, where my father comes from, to the municipality of Boticas.

In this new instalment of my long-term project, ‘The Elephant’s Foot’, I dive into the history of uranium mining, one the many elephants hunted in Portugal. As I was researching the topic prior to starting to photograph, I was reading books about nuclear power and Chernobyl. This is when I found the expression ‘elephant’s foot’. Originally, the elephant’s foot designates the large mass of corium found beneath reactor 4 of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. That extremely radioactive mass was named like that because it resembled the foot of an elephant.

I thought using this expression as a title was interesting not only to connect this work to ‘The Land of Elephants’, but also to underline the connection between uranium, radioactivity, and nuclear power. In my new project, the elephant’s foot refers to a mountain of tailings – approximately 1.39 million m3 in size – laced with traces of heavy metals and radioactive materials, birthed by almost a century of uranium extraction.

‘The Land of Elephants’ is mainly shot in black-and-white, while ‘The Elephant’s Foot’ is shot in color. What made you decide on black-and-white initially, and why the switch to color?

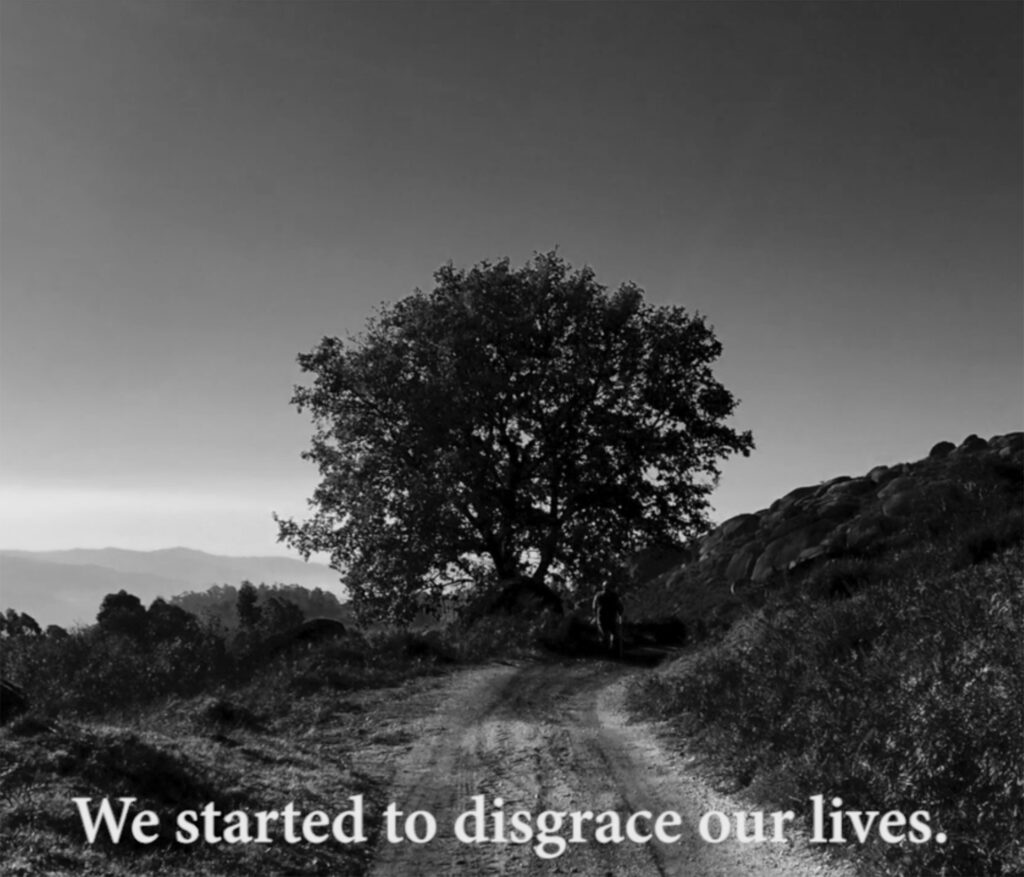

‘The Land of Elephants’ was guided by a strong questioning of the materiality of photography, its roots in extraction, its modes of production and its ecological impact. I could not conceive of photographing a territory facing an impending threat of open-cast lithium mining with a digital camera. It was a no-brainer. I opted very naturally for the use of a medium format camera, with no batteries, and decided to use my stock of expired black-and-white film rolls, some of which were then processed with expired chemicals. Black-and-white felt in line with a Portuguese monochromatic visual tradition. And really emphasized a sense of imminent tragedy.

In the end, this work combines black-and-white analogue photographs and color satellite views of the scars left by previous mining operations across Portugal. The juxtaposition of these visual registers – one in color, the other in black-and-white – helped me construct an environmental timeline, inducing a double gaze: in color, to the permanent damage inflicted on the landscape in the past, and then in black-and-white, into the future, with its impending threats of further destruction.

Since ‘The Elephant’s Foot’ deals with the permanent damage caused by mining, it made sense to opt for the use of color, though I was not reluctant to use black-and-white since the effects of industrial and radioactive contamination over time are unpredictable.

The use of color was ultimately dictated by the territory itself, and the extreme sense of disorientation I experienced/still experience when I stroll around the elephant’s foot. At the elephant’s foot, the danger eludes the senses. Neither the eyes, nor the camera can sense what is going on; it is very disturbing. Color, its possible manipulations, offered me a tool to try to convey a range of contradictory feelings one may experience when at the elephant’s foot, a beautiful place, where water flows, flowers grow, and people continue to die, victims of the lasting impact of uranium mining.

I really feel that sense of impending doom in the black-and-white photos. I also recognize it in the description on your website, which uses words like ‘salvation’ and ‘omens’, and asks: “But who could fail to read the sermon in the rocks of Barroso?” There’s a biblical layer, almost apocalyptic. Was this religious aspect a deliberate part of your project?

It was deliberate. Portugal is known to be a very religious country. Religion helped the fascist regime rule the country for more than 40 years, and it remains a very important component of Portuguese traditions and identity.

A lot of people still put their fate into an invisible entity’s hands instead of taking their destiny into their own hands and fighting to halt projects that will undoubtedly destroy their lives. The use of a religious language was meant as a criticism of this passive behavior, which allows governments and corporations to get away with their crimes.

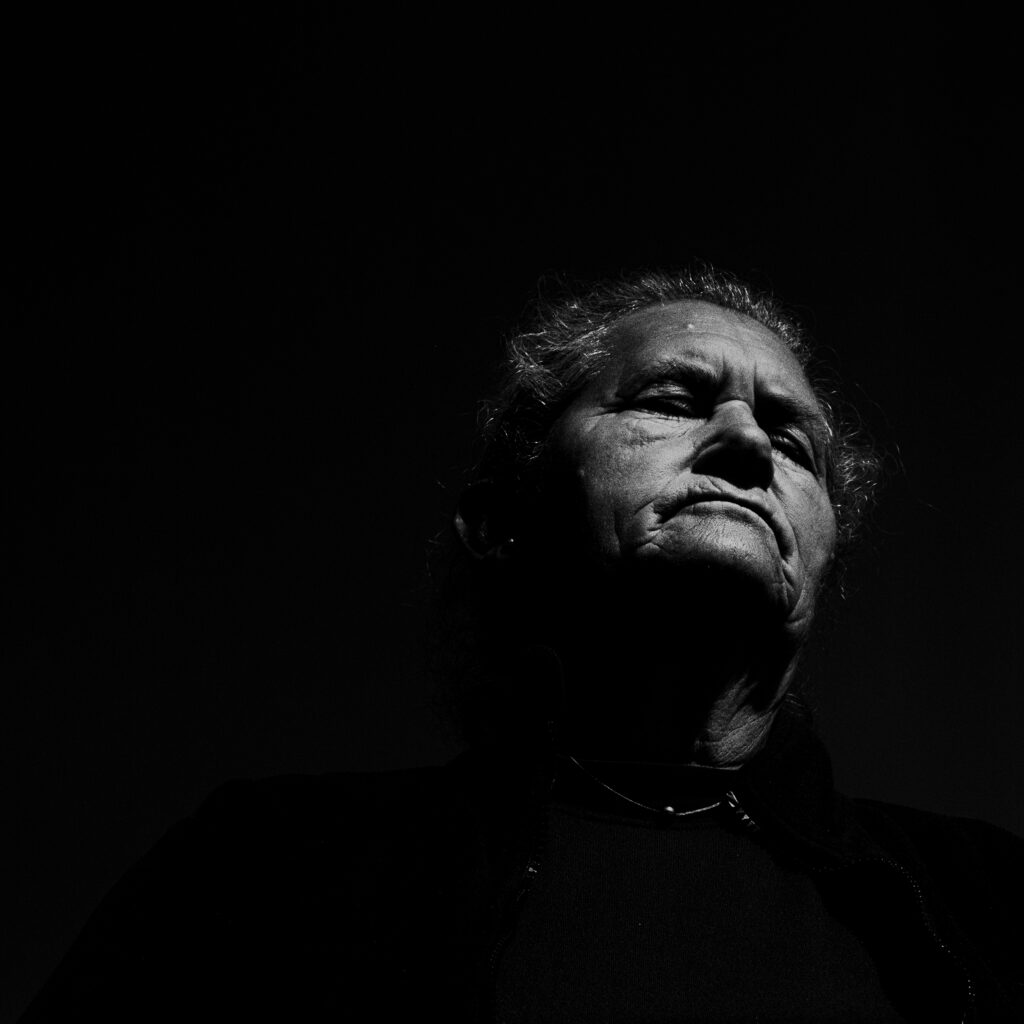

The portraits in this project all are taken from a low angle, looking upwards. Is there a specific reason behind this composition? And how did you approach people for these portraits?

Prior to starting the field work, I did a lot of research of all sorts. I looked at a lot of images, I watched a lot of movies. One movie that really impressed and inspired me was Dziga Vertov’s Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass. In this movie, Vertov celebrates Stalin’s industrialization plans and, particularly, the exploitation of coal to achieve them. The camera work is beautiful, but what struck me the most was how people’s faces were framed from a low angle to convey a sense of grandeur and hope in a prosperous future.

I thought it was interesting to use Vertov’s visual approach to frame people’s faces, but with a different intention. If Vertov was promoting industrialization, coal exploitation and progress, I wanted to take a different stance, i.e., question the promises that are being made in the name of green transition.

In ‘The Land of Elephants’ people don’t trust that resources’ exploitation will result in a bright future, because a lot of elephants have been hunted in Portugal and their corpses are still bleeding out in the open. That explains why in my portraits, the faces are engulfed in darkness.

In Boticas and Montalegre, people challenge, question, and resist mining projects that would be devastating for the region, and ultimately the country. So, it felt important to place these guardians of this endangered territory, one that is dear to me, at the center of the picture, to put them on a pedestal. I must confess my admiration and utter respect for people who live with the land.

Obviously, it would have been impossible to make these portraits without taking some time to exchange with the participants. This is one of the things I like the most about photography and long-term projects; it is the access to living archives. By this, I mean that I am always surprised by all the stories people are willing to share, because a lot of times their personal stories inform us so much about larger stories. This is one aspect that I wanted to underline in ‘The Elephant’s Foot’ by collecting the participants’ oral memories of the mine.

‘Forgotten Wars’ deals with the Portuguese Colonial War and the wounds it left on your father. You describe the events of the war as being “swiped under the carpet of a History that only wants to remember its glory.” I was wondering if you could tell a bit more about how this war is remembered (or not) in Portugal today, and about how people reacted to this project.

The conversation around the Portuguese Colonial War is quite binary. There are those who see all those who partook in the war as fascist villains, and those who see them as heroes. I often feel that there is a tendency to simplify, and in some cases to re-write history, on both sides, which ends up being detrimental to the emergence of a nuanced discourse that could open a constructive discussion.

This binary and polarized discourse, not only contributes, to a certain extent, to nurture resentments and ultimately racism, but also makes it complicated for all the victims of the colonial war, on both sides, to be recognized as such, and therefore receive the support they need and deserve. If you are a villain, you deserve whatever pain you are going through, you don’t have the right to complain. If you are a hero, you don’t complain because you are a hero, and it is well known that heroes do not suffer from trauma.

When I made this project, I applied to various photo contests in Portugal and reached out to some people in the photo industry to present it. I received no reaction or encouragement. It was more like radio silence. It happens a lot, and that is part of the ‘game’. I think the timing was not right and the nuance, sadly, unwelcomed. I stopped pushing this project, partly because of this, but also because after a while my train of thoughts and this work raised new questions and there were things I wanted to share with the world. And ‘The Land of Elephants’ happened.

Last November though, ‘Forgotten Wars’ was one of the laureates of the Prix MBP x On Stage Photography Award x Photo Doc. This made me dive into my archive and who knows, because the colonial war was mentioned so many times by the people I interviewed for ‘The Elephant’s Foot’, maybe I will resume pushing it.

Some of the photos in this project depict trauma as something that prints itself onto the skin (yet actually remains invisible). What was your approach to visualizing trauma?

My approach was manifold as psychological trauma is very difficult, if not impossible, to represent. That’s why ‘Forgotten Wars’ ended up combining photographs, archives, video, and drawings.

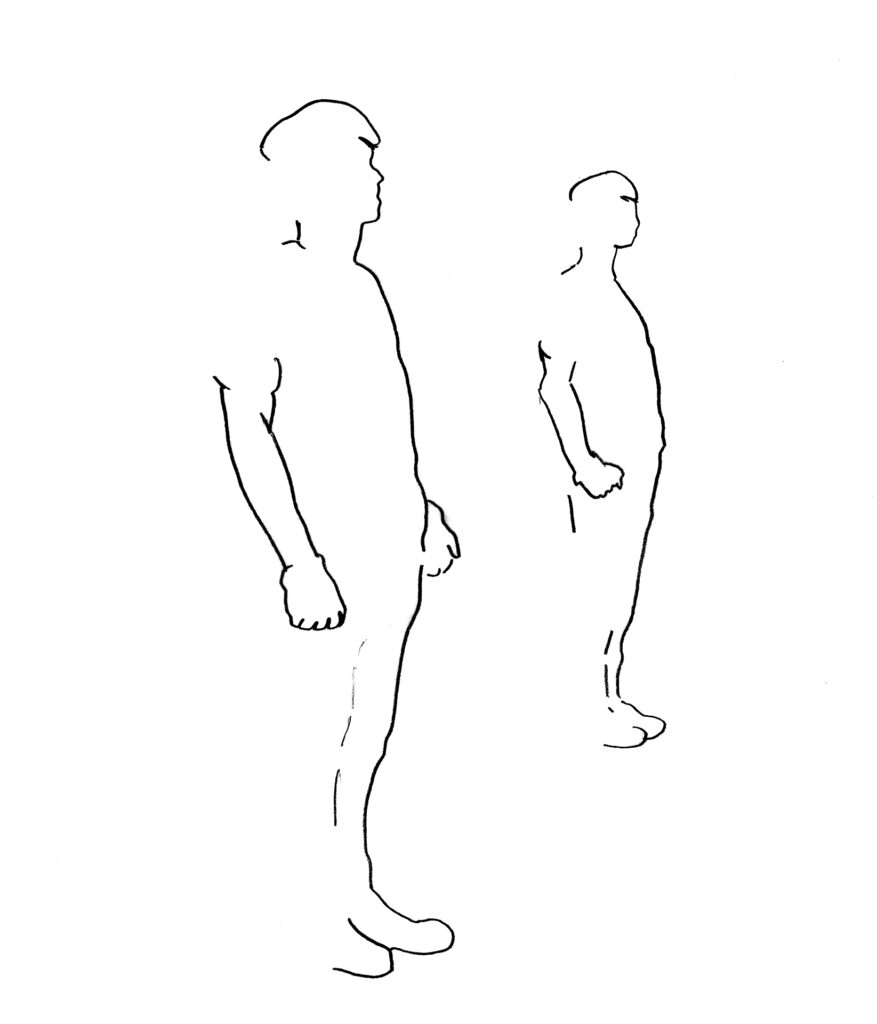

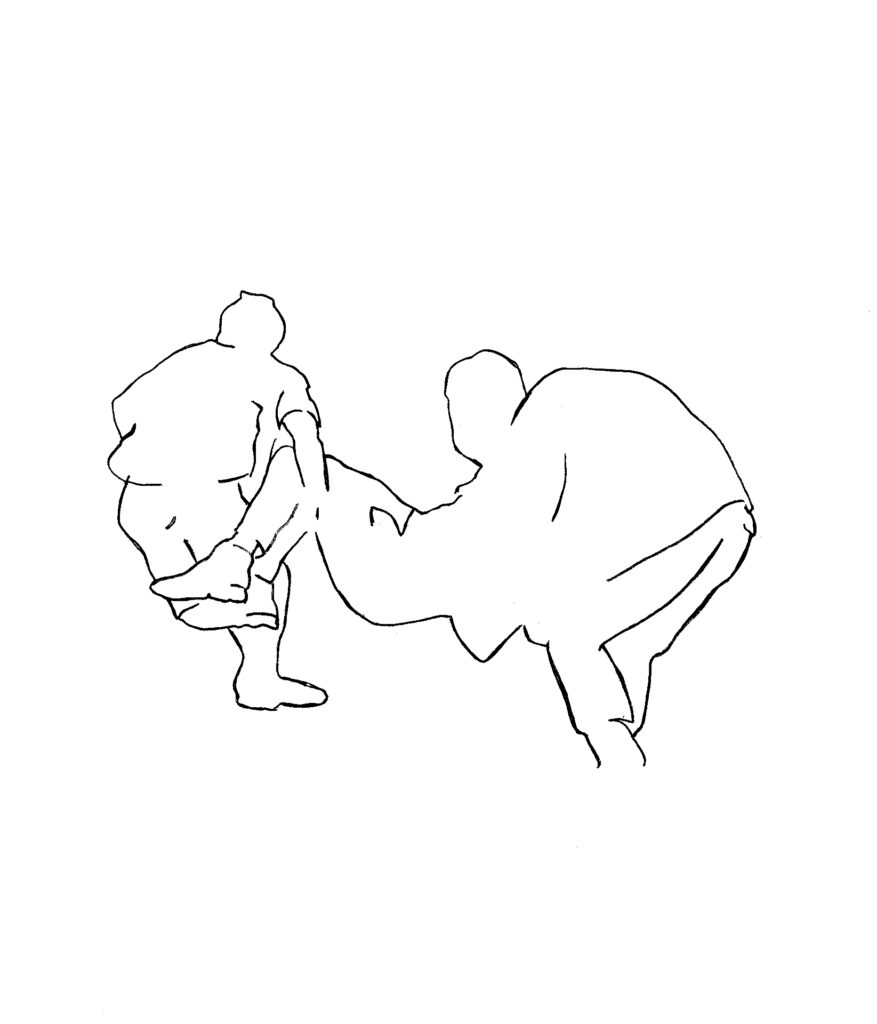

This project takes the image of a dead body as its starting point. When I was only five years old, I discovered a photograph of a young man in a photo album my father brought back from Mozambique. He is lying down, a black thread coming out of his nostrils. Something comes out of his stomach, but I can’t understand what it is. Hands appear at the four corners of the image. Among them are the hands of my father, then aged 20. The hands seem to be trying to lift the body. For a very long time, I did not understand this photograph. To this date, I am still unsure whether I understand.

Starting with this photograph, I was naturally curious about my dad’s hands and body as archives, or rather, as carriers of trauma. I wanted to summon individual and collective memory to understand how the war disrupted a generation of men, leaving its mark on my father and haunting his nights forever. I had noticed that my dad was prone to nightmares but did not make a connection until then.

I asked my father to tell me his story, and the story of the young man in the small photograph. I recorded him on camera. But faced with his many silences, I asked him if he would agree to be photographed in the studio. He agreed. Looking back, I think we were happy to spend time together and to create safe moments for the two of us. In the quietness and darkness of the studio, my father’s body began to reveal stories of war, although at the time I did not realize it.

It is only when I immersed myself in archival photographs of soldiers of the Colonial War, simplifying their compositions with pencil strokes, that I realized that each pose my father took instinctively in the studio was revealing how war had inscribed itself in his body. The drawings that resulted from this process of simplification of the archival images, anonymous silhouettes stripped of faces and weapons, served as a framework for understanding the photographs I had made with my father.

Your family left fascist Portugal for France, and you still live and work in Paris. How would you describe your relationship with Portugal, and how does living abroad influence your ability to ask critical questions about the country’s history and modern day politics?

That’s a very interesting question and I am glad you asked it. I have been thinking a lot about this duality.

After my parents fled to France during the dictatorship, they had nourished the dream to return to Portugal should the fascist regime implode. In 1974, the Carnation Revolution ended the regime, but political instability ensued. My parents were waiting for the right conditions to return when the news fell: my mum was pregnant. It was me. We were in the early 80s.

At the time, we had family in Portugal; we still do. My parents saw how they struggled even after the Revolution. A lot of houses had no running water, no electricity. The medical system was terrible. Schools were far from home. The perspective of finding a job with a decent salary was remote. All things considered, my parents decided to stay in France and renounced their dream. They wanted the best for the baby on the way.

I am a dual citizen from France and Portugal. I am committed to both countries. I have been going to Portugal since I was born at least once a year. I am fluent in both languages. I have followed Portuguese studies from primary school to college. I vote in both countries. I try to spend as much time as possible in Portugal.

I probably feel compelled to make work about Portugal, and ask critical questions, because I inherited my parent’s unfulfilled desire to return. Let’s be honest: France provided us with opportunities that did not exist in Portugal, but they came with a price. My parents suffered from racism; I did too. We had to lay low, work the double without complaining. We lived in precarious conditions. I resent France for that, but I resent Portugal even more because it did not care for its children, it made it difficult for them to stay, or return. Unfortunately, this observation still applies today if you look at the emigration trends.

France is far from perfect, but there are a lot of good things here. It gives me a frame of appreciation of what a country can do. It is from this distance that I can look at Portugal. When you photograph, you need a certain distance to make the focus. I like to think that looking at Portugal from France is my focal distance to get a clear image of the country.

Lately, I have come to the realization that at the core of it, there is an atavistic need to understand where my family comes from. Only then will I be able to understand myself. That’s also a heritage I want to give to my son who is, like me, a dual citizen from France and Portugal.

Before joining art school, you worked as a lawyer for several years. Why did you make the shift to becoming a photographer, and how does your legal background influence your practice?

Becoming a lawyer was not my dream, but my parents’. They come from a very poor background; they did not have access to education and were forced to work at a very young age to help their families. Art school, or photography, were not considered an option for my parents; because they went through so many hardships, they wanted me to have a job that would spare me the difficulties and humiliations they had endured under the dictatorship, and later, as emigrants in France.

I wanted them to be happy, and to feel that their sacrifices were worth it, so I offered them a social revenge and achieved their dream. But was I fulfilled? Absolutely not. The shift happened after I had to deal with a health problem that led me to reconsider my life and what I wanted to do with it. This is when I decided to resume my studies and went to the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague to study photography.

I worked for several years as a labor and employment lawyer. Even though I did not like the job, I enjoyed the intellectual gymnastics it requires. Although legal proceedings seem very dry, they demand a lot of creativity and adaptability.

In my practice, I feel the influence of these years in the legal field. Although nowadays it sounds cliché to say that one’s work is research-based, in my case it’s second nature. I like researching as much as possible about my topic before I press the shutter. My reads invoke words, themes, questions, which in turn will lead to mental images. It is like building a case and a strategy to elaborate an argument.

There is also a writing aspect to the work. For instance, in the project ‘The Elephant’s Foot’, I am compiling and editing a series of interviews I led with the members of the community. I am ‘deposing’ them. Their testimonies are valuable not only to keep a record of what the mine, and the labor at the mine looked like, but also to understand the heavy price miners and their families have been paying because of uranium mining. They are written records challenging official narratives and silences around the topic of uranium mining.

More Silvy Crespo:

Photoworks article

Artdoc article about The Land of Elephants

Noorderbreedte article about The Land of Elephants [Dutch]

Interview with De Correspondent [Dutch]

Website