I was walking through the city once, and right in front of the entrance to a clothing shop, I saw this little kid sitting on the ground, playing with his toy car. The car was driving, gliding and flying in his hands, while he was totally unaware of the inconvenient spot he’d chosen. I remember how jealous I was of his unawareness and his ability to completely disappear into his own world. Somewhere in getting older, I had lost that.

For I Am Always You, an installation by multidisciplinary artist and graphic designer Isa Vink, is a research of the inner child and the things we lose by growing up. The work is Vink’s graduation project of her bachelor’s degree at the HKU University of Arts, and combines poetry, film, photography, music and book printing. The result is a somewhat sad but mostly sweet experience, a work that takes you by the hand on a quest for the child within.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The first work of yours that I saw was For I Am Always You. Could you tell me a bit more about that?

For I Am Always You is an installation that consists of a very large book and a video installation. The project started with feeling a sense of loss for the child that I always used to be, and noticing that I was looking for how I could be her again. And it – actually a big step back – all started with a minor in the third year of HKU, where I made an installation with archive material, in which the memory we have of being a kid is sort of slipping away from us.

And I wanted to find that feeling in some way – being a child – in the person I am today. So through that I came to a video installation that centers on three performances, each visualizing that feeling of being a child, so the carelessness and the clumsiness and a kind of friction with that sense of loss.

How did you notice that you were missing that inner child?

I think mainly in being kind to myself; the little kid you’re looking at. I missed it in that I noticed that I wasn’t always being kind to myself, and that in the moments I wanted to be crazy and free, there was some judgment in my head of: oh this is weird, but children do it too. So why does it suddenly become weird if you’re an adult? There’s also quite a lot of rules that are imposed on you, and as a kid you don’t think about that at all. And I felt myself missing that a lot.

Could you rediscover any of that while making the work?

Absolutely, because there was one of the videos, a kind of formative dance in a forest. It’s inspired by old tapes that I digitized, and I’m dancing on a table in a similar way. I think I replicated that three times. And the moment I was standing there… in the moment it became really spontaneous again.

And I could tell I felt awkward, because there was no music, but eventually I started humming and dancing, and it was really like: okay, you just have to surrender to it. Just be clumsy or just dance in a stupid way; it actually isn’t that bad. So yeah, I think particularly with that specific video, and in the whole project, that I did find an inner layer of myself again.

What did that search look like? What were other ways in which you went looking for that inner child?

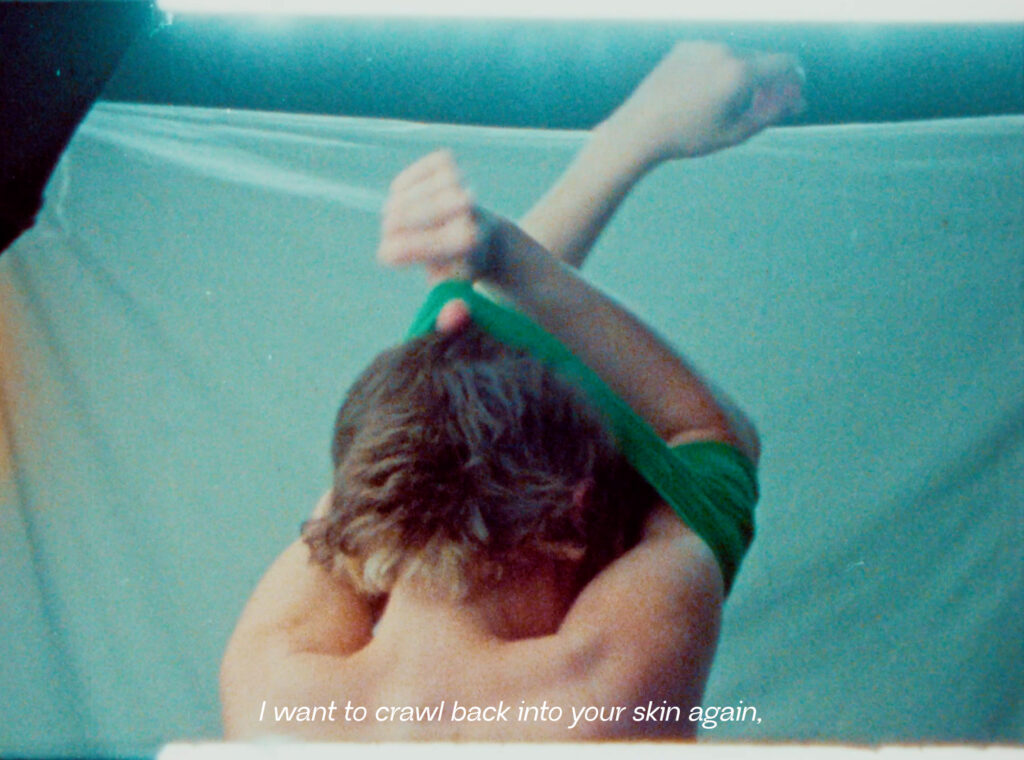

Mainly by doing the things I loved doing as a kid. Wearing a shirt that’s too small for example, because kids wear tiny clothes that adults don’t fit in, of course. But putting on a shirt that’s too small exactly symbolizes my desire to crawl back into the skin being a child, but it doesn’t work and I can’t, because it no longer fits. Through that, I go looking for other ways. For instance, as a kid I would rub make-up all over my face. Color outside the lines. As an adult or young adult, you can still do that. It just takes a different shape.

I don’t think it’s about the materialistic part, but rather about the feeling that it gives you. Being open for that, maybe.

The work was a search for yourself, but also a wider investigation into finding your inner child in general. Did you come upon any recognizable or shared experiences from other people?

I actually did. Because the project started with a whole preliminary research of what it means to be a child. And what is that nostalgia of being a child? And naturally, that nostalgia for being a child is different for every generation.

So the project is mainly based on, I think, largely my generation. But I also asked other people like: what do you miss about being a kid? When do you feel most childlike? And with all those ingredients combined, it was about looking how my experience of that loss could be turned into a more universal and collective experience.

Why do you think that we lose it?

I actually think… yeah, at the age of four, five, you’re just discovering a lot, and everything is new and super free. You’re looking at the world full of wonder. When you get older, there’s more input from your environment and more opinions from others that all matter, which also shapes your own views.

It’s also, I think, a kind of growing pains, because as you get older there are more responsibilities and you’re on your own a bit more. You can’t just crawl back to where maybe things felt so soft. But this is more how I mainly experience it, there’s also enough people who did not have a nice childhood.

I’m curious about the final shape of the work. Because you talked about the three screens with the three performances, for example. What was the reason to choose for three performances, those three screens?

The screens are really big, which means you have to sit in front of them and you’ll look at the images like a kid full of wonder. Like sitting in front of the TV at home and thinking: wow, what’s all this before me? Eventually I decided to do three, because they were very singular but also connected to each other, as in: the visitor could sit down and really look at one, but from a distance you could see all three. It works together, but also on its own. Some visitors could connect very strongly to one, for example, and feel nothing for another.

Each performance, or every video, also captured a certain feeling. Together it formed a search that also consisted of different parts. So there’s not really an ending or a beginning.

How do you divide that into three parts? How do you determine the three parts of that larger story?

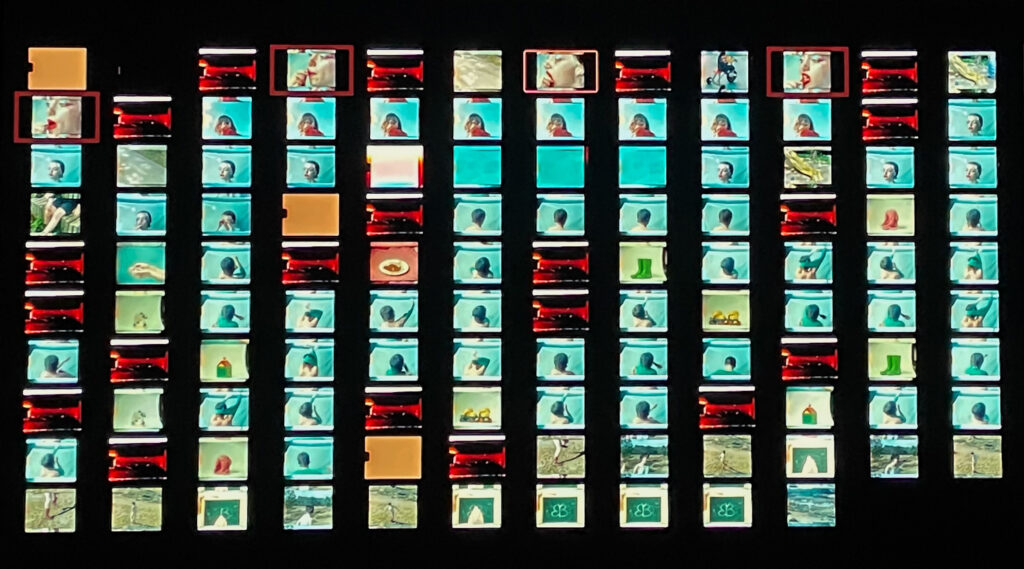

The initial idea was actually to do five. But to give some context; we shot everything on film. We worked with children, child actors, but all that footage… something went wrong. And we didn’t also film digitally, so we didn’t really have any images anymore. In the end, we planned a new day of filming, but we also decided: three screens is actually much better. Because if you see five screens, what do you even look at? You don’t really get immersed into anything.

For one, I wanted to emphasize that sense of loss and the longing to return to something, and that led to the performance of putting on a shirt that’s too small. The other was more about emphasizing the coloring outside the lines and that you also find that inner child a little bit by doing what you used to do as a kid. That was the one with smearing the make-up all over. At the same time that one’s also very sad, it contains a somber portrait. So that one feels kind of in between. And the one in the middle is a dance which focuses on how being a kid is very careless and clumsy, and that feels a bit uncomfortable, but that doesn’t mean you can’t do it anymore.

There was also a book as part of the installation. How did that relate to the images?

The book was actually more the start of this search, I had made it earlier that year. The book centers on missing that inner child and the memories you have, or the image you had of yourself, fading again. You can look at portraits, but sometimes you no longer recognize yourself in them, because you’ve created such a distance. The book is about being aware of the feeling. And through that awareness, the project became more driven by action, so a video installation in which you do something you also did as a child. In that installation, there were also all these texts on the ground, a kind of poetry, that underlined that step between the book and the installation.

It’s a bit difficult to explain now I don’t have it… now that it’s not right here.

How was the book made? What images did you use?

It contains seven portrait photos and seven poems. The portraits are all loved ones of mine, so friends, family. I’m not in it myself. And the poems were made based on letters I had them write to their younger selves. I took parts from those letters and combined them with other texts I had written. As you scrolled further through the book, the images became more faded.

So that also really contains that whole collective aspect, that collective nostalgia of missing and wanting to be kind to yourself.

On your website I saw Fear to forget about you which felt like it was strongly connected to this project. How was it a part of this?

So that was that video installation I’d made in my third year. That was in fact the very, very, very first starting point of everything, for which I very much went looking for archive materials, and to strongly reshape them and project them onto fuzzy material, with everything passing you by. The texts in that installation, those are completely made from the letters people wrote to themselves.

Each of the three projects is a kind of step.

One line that really stuck with me from Fear to forget about you is “I had hoped you would have been able to appreciate you in the way I view you now.” I saw a real melancholy in that, a sense of wanting to make things right.

I also think it’s about wanting to do the right thing for your younger self, and wanting that person to be proud of you too. But also the other way ‘round. It really feels like a connection: you’re doing it for your younger self, but your younger self is also doing it for you. And sometimes it feels like that inner child is gone for a moment, but they’re always there.

I noticed that in the poem, you address yourself in second and third person, so you’re talking about ‘you’ or ‘she’. And it felt like an interesting contract to me, between talking about yourself, but also addressing yourself like that.

I get that. Maybe it’s… I think that by addressing myself in that way, there’s still a bit of a boundary; I’m not fully her yet. But it’s also confusing, because I am actually her.

I see my younger self as… like, I imagine that I’m talking to this little girl with curls sitting here. And I think when I talk about her as ‘you’ or ‘she’, it becomes easier for me to be kind to her. But it also keeps a little distance between her and me.

So how do you see your younger self? As ‘me’ or ‘you’?

Very much as a ‘he’, that’s also a long story. But maybe that’s why I reacted to this work so strongly, from my younger self and the connection I do or don’t feel with that person.

Do you feel a connection with your younger self?

Sometimes, but that’s difficult.

It’s pretty extraordinary that quite a lot of people experience it like that, isn’t it?

It also almost feels like a kind of comfort you want to offer your younger self. Just wanting to hold them on your lap and hugging them, and wanting to tell them: everything will be alright.

So do you see that younger self as somebody that needs to be comforted?

Sometimes I do. But I really long to be a child like until I was seven. Because from seven to seventeen I didn’t enjoy things so much. I can’t look back at my high school yet with a kind of nostalgia.

Yeah, I recognize that. I think for me, that’s also where the biggest divide between myself and myself develops.

And sometimes you wonder: was it really that pleasant when I was a kid? Or is it just the idea that I want to hold onto? Did I actually look at the world with such wonder, or was I just crying all the time? I can think about this for hours.

We were just talking about all the different parts of this project, which eventually led you to For I Am Always You. You describe yourself as a multidisciplinary maker, and I’m curious how you make all these disciplines fit together. How do you combine them?

Although I have graduated as graphic designer, honestly I didn’t really know what graphic design meant when I started. I wanted to combine my text, well, in the end that was correct.

As a multidisciplinary maker, I’m trying mostly to channel emotion into poetry, and connect that to image and sound. I think I really like that combination of image, sound and poetry, because as a maker I find it most important that other people can feel or experience something with what I make. Which does come about from personal fascination.

So I see myself as a multidisciplinary maker, because I don’t cling onto one medium. I don’t want to only make a book, I want it to become more of an experience for somebody, and with a book that also takes sound. Otherwise you’ll read it, but I want people to truly feel it. Sometimes you can’t fully feel things when you’re just reading it, and I think that image, sound and poetry are a very strong part of that.

So is poetry the thing that comes first for you? Or does that change a lot?

Hmm. Sometimes it is. But often it all blends chaotically and gradually. Usually it starts with a personal fascination and texts that I’ve written. But with this project, I had made the images first and wrote the texts based on that. So that was a very different process.

I switch it around all the time, it’s not like I have a step-by-step plan. Sometimes it’s also about time constraints.

How do you experience the boundaries of those different disciplines? What can you express with one, but not with the other?

Videos for me are more about sketching a certain image, or to get an idea of what something will look like. Poetry and sound is really to convey that emotion… another really good question. Wait, could you maybe repeat it?

How do you experience the boundaries of those different disciplines? What could you express through film, but not through sound for instance? Or the other way around, what can you express through poetry, but not through film?

I think addressing people, creating a collective experience, to me is mostly in sound and text, not yet in image. Maybe that will come, but the image might not necessarily hold that power for me. I think it’s indeed mainly sound and text, that’s to evoke that emotion that we feel collectively.

But the images of the video installation are also very poetic. But also very vague. So there’s a kind of connection between vague and literal, and the images… this is actually pretty complicated.

You mentioned the collective experience a few times. What is a collective experience for you?

I see a collective experience as creating some sort of awareness in people. Evoking a feeling and an emotion. What I showed in the project, that’s also largely how I experienced it and that’s a specific thing, but because it’s so much about nostalgia and being a kid, it’s much bigger than that. It’s a subject that really concerns everybody; everybody’s been a child and has an inner child within, and some have lost that a bit more than others, or carry it with them more than others.

The collective experience is actually in the larger that’s hidden within… within the small…

I also came across a workshop you gave earlier this year, ‘2059’, in which you had children write letters to themselves for later. And I really saw a clear connection between this project and your other works. Was that on purpose?

No, I did that together with Sterre Roza. We’d given workshops for freshmen at HKU, and we were asked if we wanted to give a workshop with the theme ‘2059’. Then we had the idea to make a little box that you fill with everything you cherish, then you bury it and dig it up again in a number of years.

The funny thing is also that we prepared that workshop for children, but that wasn’t clearly communicated on the website, so the only participants were 40-year-old women. That was really fun, and they also really enjoyed doing something childlike like that again. So looking back, it was actually a really fun, nice result that grown-up women could be a child again for a moment.

It does really sound like something that would conjure up that same sense of wonder you have as a kid.

Yeah it does. And they all tried these new things with scissors, and they also had to make a self-portrait in two ways: one of how they looked now, one of this many years later. And write a poem to themselves. All of that went into a little box, which we locked with a seal. That went into a little bag, and they can dig it up again in 2059.

Did you also make a box yourself?

Yes, but I haven’t buried it yet, haha. It’s still at home. But yes, I did participate!

Do you want to tell me anything about what’s inside?

Two portraits. And I recreated my childhood plushie; I made a drawing and put that in. I’ve had it since I was a kid and I still sleep with it, I could never get rid of that. And a whole list of things I cherished: I think my family, and also looking at the world with wonder, I actually don’t remember the rest. You can see it in 34 years!

We already discussed poetry a little, and I saw this work of yours that included a poem, Hungry Lovers. I had a very physical reaction to this work, and I was curious if you could tell me more about it.

Yes, this is already a little while ago, but… we had the assignment to make a one-minute-video. You were free to do what you wanted, you could also use found footage, but I wanted to film everything myself. So the whole thing is filmed with my iPhone. And I really just wanted to do things that we consider to be dirty: why do you cover yourself in mayo? Why are you standing barefoot in minced meat? Gross, but so cool!

Sometimes, I really enjoy combining such absurdist things with a very classical poem, or something very contradictory, and look for the connection in that. Because sometimes it feels as if two things don’t belong together at all, but that doesn’t mean you can’t bring them together. It might not’ve made you think of a love poem, those images, but when you include such a text, you get a totally different connotation and it takes on a whole different meaning.

Playing around with the meaning of image and text is very interesting to me, and also how we look at that; what kind of impression we leave behind. I think it’s kinda funny it gave you such a physical reaction.

Is that what brought you to graphic design? How did you come to the realization that you wanted to do something with image and text?

I’ve been writing poems and stories, I think, since I was twelve. I really loved it, but I also noticed that image really did something for me. I also did a preparatory course at ArtEZ University of the Arts, and that’s when I noticed that I liked graphic design so much because you can connect text to image. I also really loved drawing and painting, and especially combining all those things was really interesting to me.

During my bachelor’s was really when I realized that what I thought was graphic design, wasn’t graphic design. Graphic design is mainly communicating the story, and that can be done in many ways. The bachelor’s is pretty abstract, so we also worked with one-minute-videos, but the focus was largely on book design. I’m happy we got to make videos, ‘cause that’s how I realized that I felt a fascination and passion for film and installations. Making books is also really fun, but sometimes.

After Hungry Lovers I also read the poem ‘Storytelling’ on your website, and I saw that same physical experience. Had you already considered that? Was that a deliberate continuation?

I think my fascination at that time was very much in the absurdist and verbalizing something that didn’t really feel right. So that poem is written with Artificial Intelligence. It was an assignment in which we had to write a poem using ingredients from a workshop by Heleen Mineur. By the way, I’m not a proponent of AI, but I’d only just started and didn’t know yet what impact it would have. I just wanted to add that.

But you had to ask AI questions, and you would take things from that. Using that, you created a whole new text. That also resulted in that when you read the poem, sometimes you kinda feel like: what the hell am I reading? What does this mean? And with poems, it can feel so nice to stretch that a little. Having someone’s attention without them fully understanding where it’s going.

It’s also nice that poetry gives you the space to say something, to convey something, in a way that can be vague.

The poetry in For I Am Always You is much more direct, and less absurd. That fitted the project more, because the images were already more abstract. So to really get the message across, it was logical to write the poetry more in that way. I also write in many different ways.

What are your inspirations? Is that mostly by discipline, or are there multidisciplinary artists that really speak to you?

I think for inspiration mainly photographers and filmmakers. I also get inspiration from books, or certain sentences that people have already written where I find the words or the structure very interesting. Then I’ll look if I can write that differently somehow, and try to add things. I’m really not against working a lot with things that already exist, but it has to be molded in such a way that it’s no longer the original.

I actually mostly take inspiration from everyday lives and how people interact with each other: tiny details, conversations people have, but also the love that the elderly share with each other and how small children behave. In terms of artists, there’s a number of films I really love, because they verbalize or visualize something in a very special way.

I also really enjoy the photography of Rineke Dijkstra, because she works with flash a lot and I really love photos of a moment in between, and that capture a certain awkwardness. It shouldn’t be too perfect: those little uncomfortable things and tiny details I really find very inspiring.

Do you enjoy awkwardness?

I think it makes us interesting. Sometimes I hope that I’m perfect, but I’m not perfect and I’m also awkward sometimes, and sometimes I just love it so much when other people are also a bit awkward. My friends and I always say about people: they really ain’t right. But we mean that it’s so amazing that they’re completely themselves and we totally love that. Other friends sometimes don’t understand what we mean by that, but whenever we say that, it’s actually that that person is awesome or just a little awkward. So that awkwardness… yeah, no, I really love that.

There’s also a bit of that inner child in that. Kids are a lot better at just being awkward and not bothering too much with norms and values.

Yeah, and just… I think when people or kids are awkward, it’s also just a way of being yourself. It’s accepting that that’s a part of it.

Do you think you embrace your awkwardness?

No.

But it’s actually also something, you think… why is it so bad to be awkward?

Yeah, that’s a good question. I don’t mind if other people are awkward, but I do think it’s the demands you make of yourself versus the freedom you can offer others. And I think what I demand of myself is to be myself without standing out too much.

Do you mind standing out too much?

Yes.

Interesting… I’d love to ask a lot more about this. Maybe I should interview you sometime! Because do you also have a preference for art… where there’s a kind of perfection instead of the awkwardness?

No, not necessarily. I also find it really – maybe because of that – very admirable when art causes a bit of friction, when I don’t entirely know what to do with it, when it steps out of line.

At this stage the interview got interrupted by a little girl walking her cute dog.

Good thing we went to sit outside.

You know what I mean, isn’t this lovely? Sometimes that can make me cry a little, to be honest. They fit together perfectly, the kid and the dog.

Before the interview, you said that a lot of people keep asking you: now what? And I’m also kinda curious actually.

I’m currently working in a film theatre, because right now it’s also mainly about making money. But now what… soon I’ll probably also have a studio space – if it goes through – with some friends. I’m really eager to start writing a lot again. If everything goes well, I’ll also have an exhibition in March where I can show my graduation project, which is really nice. And I would really love to just continue my studies, I think there’s still plenty to learn. I’ve never been good at making choices, so I want to do a lot of things. I want to work on film sets, and I think it’d be super cool to learn more about creative writing, or to do more creative writing in general. To assist on film sets, or maybe become an intimacy coach on film sets.

And perhaps film projects again. Because it really was… this graduation project was the first time I actually worked with a larger team. Usually I do everything myself, so that was totally new. And my first time shooting on film, that was also thrilling, but it truly was so much fun and a really nice, beautiful experience. I absolutely want to do that again. I would just really like working in a collective. And maybe release a poetry collection at some point. But I also really want to work in the garden, and be in the kitchen, and be with people. So a combination of… a combination of giving something to others and making my own projects as well. I don’t want to be a full-time multidisciplinary or autonomous artist, I love working with people.

But that’s what this year is for: to kinda figure it all out.

Final question, I kept putting this one off: so you shot For I Am Always You on film. Why did you choose film?

I think film has a feeling that you don’t get with digital footage. Even if you’d recreate it, it never feels the same. And I love things that have a vintage or old look. All that video footage from my youth was shot on one of those camcorders, so the idea at first was to also recreate it exactly on a camcorder. But in the end I’m happy we decided on film, because it really has such a charm. Film doesn’t actually look perfect as well, and it embraces not being perfect. I think that adds a nice layer to the project and it also feels as if you’re looking back in time, but it’s happening right now. It has something symbolic.

These really are good questions, because I thought about the project a lot, but now I’m really like… oh, yeah…

More Isa Vink: