Over the last 10 to 15 years, Jeremy Starn has amassed an impressive body of work that constantly expands and evolves beyond its limits. Starting out as a photographer, his practice now also includes sculptures, paintings and mixed media installations. As he keeps moving in new directions, the through line in his work remains: examining our relationship with the natural world. There are endless ways of approaching and visualizing this relationship, and I love (and envy) Starn’s ability to find perfect stories, examples and metaphors, such as replicas of fading cave paintings, invasive species, and ‘token trees’.

Although sometimes bleak, I find these subjects to be thrilling in their aptness and their layeredness. They’re self-contained stories that are just begging to be explored; to be uncontained. The variety and expansiveness of Starn’s artistic practice, to me, seems like a continuous search for the best ways to uncontain them. The resulting works invite you to explore, to engage, to reflect, not (just) by being bleak, but by being layered and funny and beautiful.

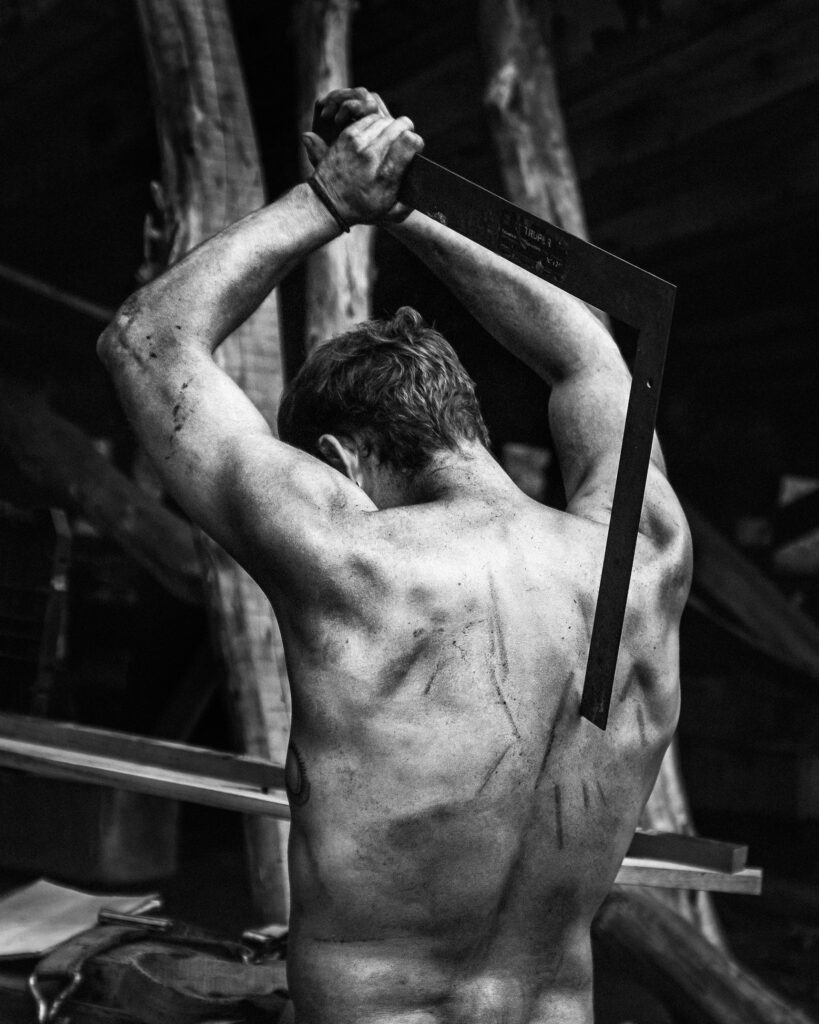

For your project ‘Displacement’, you spend three years in Costa Rica to document the construction of the Ceiba, a wooden freight ship intended to provide zero emission cargo transport in the Americas. How did you discover this project? What made you decide to document it so extensively?

I was working as a research assistant at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Gamboa, Panama and as part of my visa renewal I went to volunteer in Costa Rica at the shipyard. I had sailed on traditional tall ships in high school and I really enjoy the community it brings out in people, so when I heard about the project I was really excited to check it out. I initially heard about the ship from my cousin who is a professional tall ship sailor and was one of the starters of the project.

I stayed for a month, went back to Panama, completed my contract, but when thinking about what I wanted to do next, the shipyard was calling me. I went back in August 2019 and planned to stay a year, but then COVID hit and it turned out to be a pretty great place to be. One year turned into three years with some breaks after COVID subsided.

I’m curious about your role within that community as a photographer. How did your relationship with the people develop through the years, and how did that influence your photographs?

It started as a really small project, with mostly volunteers that were given tents and shacks to live in and rice and beans. Initially I was just a volunteer photographer and making some social media videos for them. As the project grew and investment money started coming in, they realized the need for extensive documentation to help with fundraising and for posterity. They were able to offer me a small stipend to help with marketing, communications, fundraising, report writing etc. while I was photographing.

It felt good to actually be part of the team as opposed to strictly an observer. I got to know more about ship construction and what it took for the shipwrights to construct such a massive wooden ship in the middle of the jungle. I wouldn’t have gotten the pictures I did if I was just visiting. It took time to feel comfortable with everyone, understand the dynamics, and figure out what story I wanted to tell.

As a photographer and researcher, you’ve photographed communities all around the world. Do you have any methods or tactics for positioning yourself within new environments and engaging with locals? How do you establish the trust needed to take a portrait of someone?

I’ve found that a good portrait usually requires a great deal of trust. Most people don’t mind their photos being taken if they just know who I am and why I’m taking photos. I always talk to people without the camera first and just ask them questions about themselves and what they’re doing. Taking portraits for me is a sign of respect and if I can convey this feeling then people tend to really open up.

A major theme in your work is the relationship between humans and our environment. What sparked your fascination with this relationship? How has art helped you explore this theme and deal with your own relationship with nature?

I’ve always been interested in relationships between human and non-human as I put it. A lot of it comes from how I was raised. My father was a geologist for the United States Geological Survey and my mother was a landscape designer, so nature and how people interact and manipulate it, were just common conversations at home. I think that there are a lot of different lenses you can look at it through. Philosophically, humans are nature, yet something is different. What is that? Why and how do we create these false divisions? In very straight terms, the scale of humanity changes the way the planet operates. Creating new kinds of food, inventing animals, altering weather systems, draining resources from inside the earth; these are monumental achievements, but also seem very unsettling to me.

Creating artwork about this has really helped me discover my own morals and ethics. I see a lot of environmental hypocrisy in the world, saying one thing and then doing another – I do it all the time, but creating work about this has really given me the time and space to explore many different viewpoints and considerations. I think it’s important for everyone to question what they believe in, if for no other reason than enhancing your understanding of why you believe something.

There’s also the recurring element of water in your work; projects about ships and rivers, and works such as Weaving Water, Water photos, and A Fools Errand, which is a visual dialogue with water itself. What makes water so interesting to you as a subject or metaphor?

This didn’t become clear to me until recently actually. A friend pointed this out and it pleasantly surprised me that I hadn’t noticed the theme. Of course it makes sense though, I love water, ever since I was a kid. Swimming in the creek, boating, swim team, fishing, sailing, I’ve always loved being out on the water for so many reasons. In terms of the artwork, I think that it’s a very malleable and powerful metaphor for time and life. Well first, it is essentially life. It’s the most important element of life that we know of. I also like that it’s tangible yet amorphous, like life. We can define it, but then the next second it’s changed shape. I’ve always been drawn to the saying “you can’t step in the same river twice”. I think it’s a really powerful reminder of how the only constant is change.

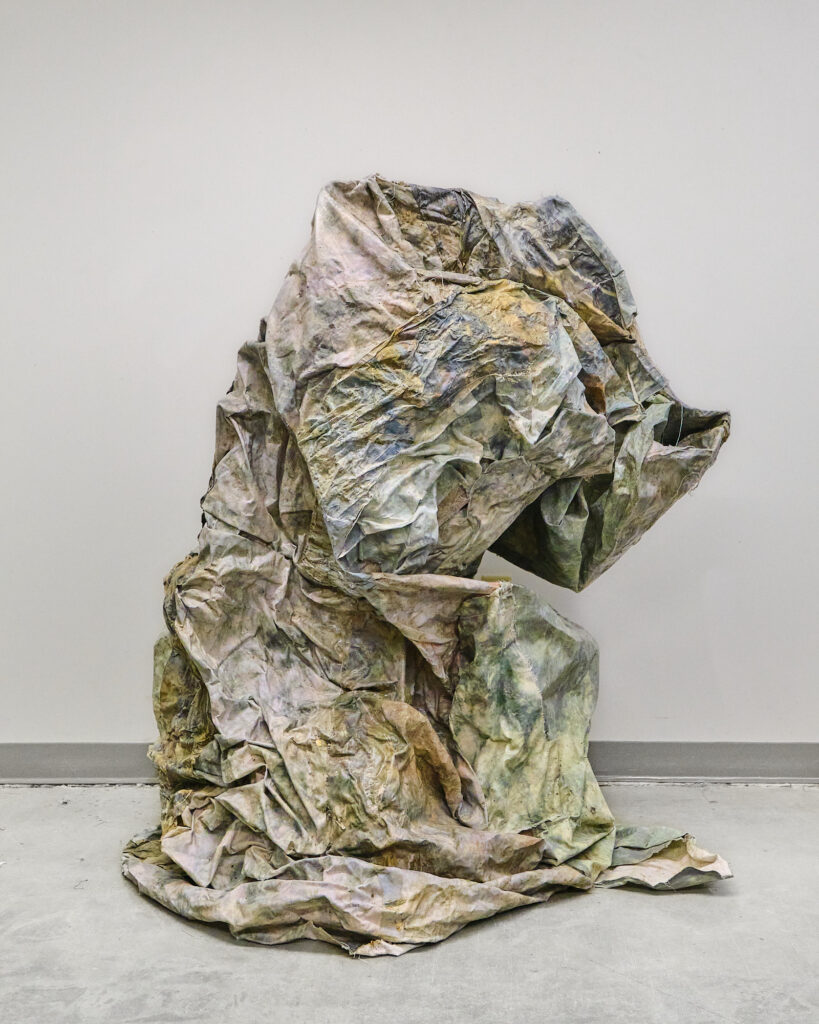

In my photo installation A Fools Errand, I tried to explore these ideas by photographing the exact same spot in a stream for months on end. The tripod stayed in the exact same position and the camera framing never changed. I would tweak the exposure time slightly based on the time of day but that was it. I took these thousands of abstract photographs, turned them black-and-white to emphasize the reflections, and printed them on a very large scale. To add to it, I’m really interested in making photographs more sculptural, so I adhered the photos to PVC boards, cardboard tubes, plates, tiles, strings, and installed it all in a way that was sort of jutting out from the wall. The intention was that it would change as the viewer walks around the piece, just like how walking around a stream brings out new perspectives within it.

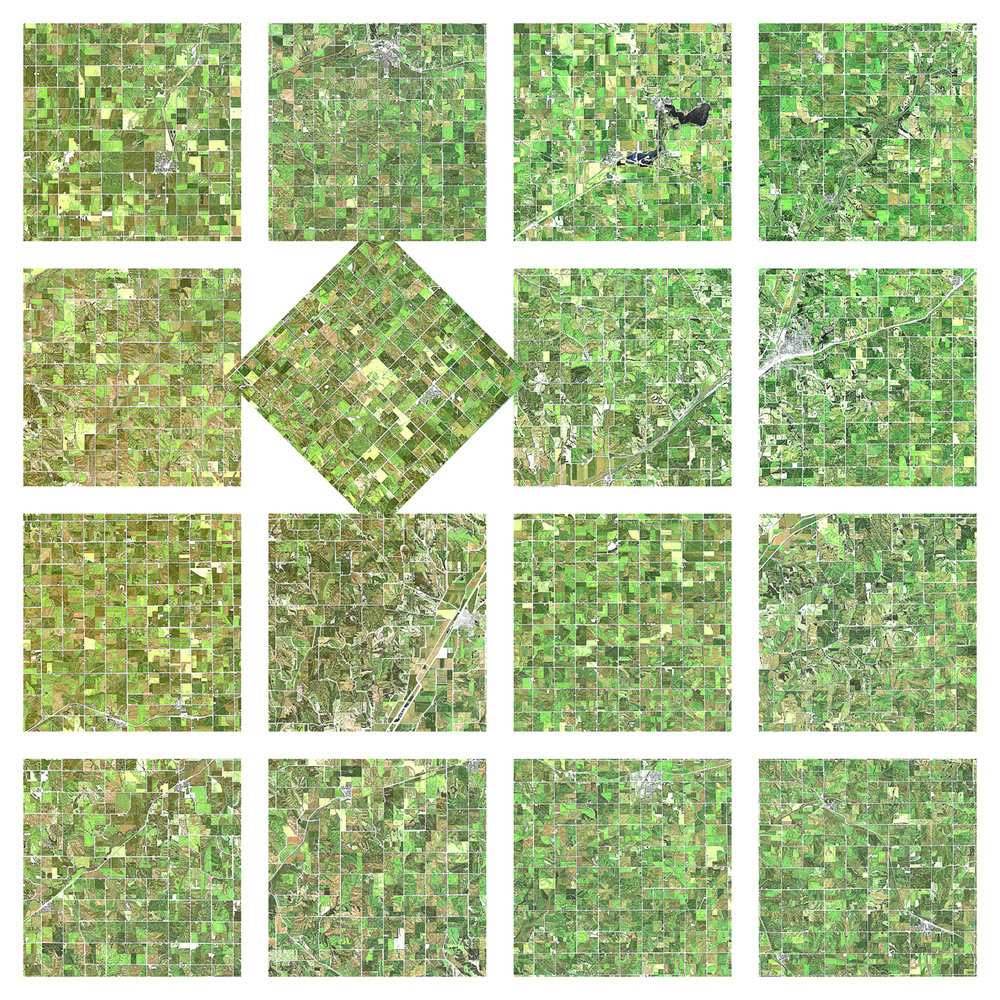

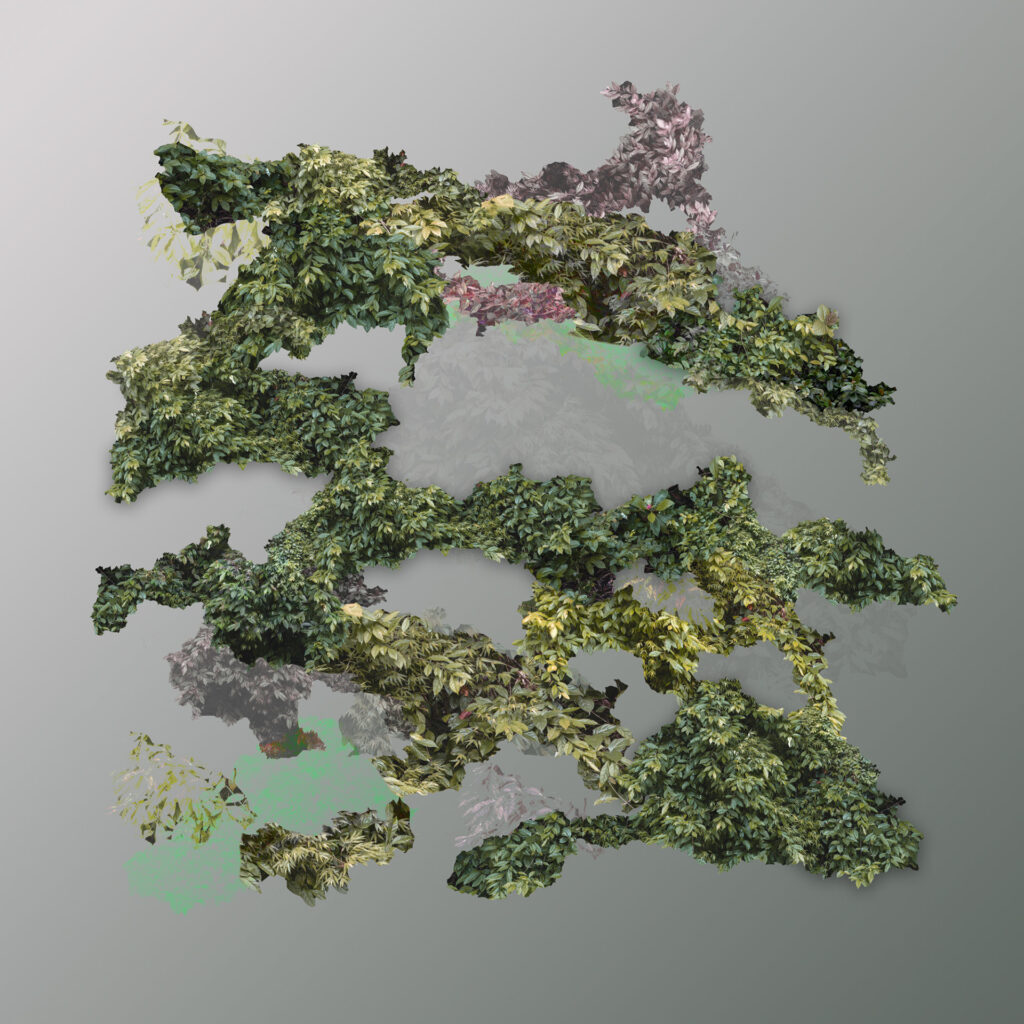

token tree presents a collection of Google Street View images of single trees on lawns in the dry American Southwest. How did you collect these images? Was it simply a case of clicking through Google Street View a lot, or did you have a more sophisticated method?

I spend a lot of time on Google Earth; it’s a little hobby, just exploring places. I was just going through suburbs and when I noticed that most of the subdivisions have this one pathetic looking tree planted in the front yard, something just clicked. I started by manually going through newly built suburbs where it’s most clear, and then the more I thought about how odd it looked the more research I incorporated. Why one tree? What is its purpose? It’s not for shade, they’re too small for recreation, it’s purely aesthetic, and in the American Southwest they really look out of place.

So I started narrowing the focus to suburbs in drought stricken areas, and on streets that are named after trees. I used Gemini to search streets named after trees in drought stricken areas and honestly it’s such a common practice it was easy to find hundreds. From there it was just narrowing it down to the most interesting looking ones.

Although you consider yourself a photographer first, in recent years you’ve started expanding your art practice with sculptures, paintings and installations. What do these different art forms allow you to present or communicate that photography (by itself) doesn’t?

I’ve always been torn between the very practical use of photojournalism in telling human stories that can have direct meaningful impact, and these more philosophical high concept contemporary art practices. Due to the type of grad program I’m in at the moment, the conceptual installation work is of more interest right now. The two approaches can have similar themes but they are usually shown to different audiences. The photojournalism is for magazines, newspapers, and generally online, and the contemporary sculptural work is for universities, museums, and galleries. There’s crossover but that’s how it typically plays out.

Because of where I’m at, it’s a lot more interesting to play with form, and experiential installations, and new ways of presenting imagery.

I was a little surprised to see that you’re currently working on getting your Master’s degree in Fine Arts. What prompted you to go back to university after already working as an artist for so many years?

I always knew that I wanted to go back for my MFA eventually. I was just waiting for the right time but I also, wrongly, felt like I needed to have the right project or direction in mind before applying. I eventually realized that since the timing was right, I should just pull the trigger to do it, without having in mind what I wanted to explore. And that was the right decision. I figured out what line of research I wanted to explore almost immediately, and I’m very happy that I decided to just go for it instead of waiting for the right time.

Something that someone said to me put MFA degrees in a different context to me which made a lot of sense. They said: don’t think of it like school so much as a three-year residency. My program is fully funded with a stipend, so I’m getting paid to make work, I have access to amazing facilities, and a network of amazing artists to bounce ideas off of, so for those reasons I recommend it to anyone. As someone interested in more conceptual or experimental work, I can only go so far by myself. I need to be surrounded by others that are also pushing their own mediums in order to have these wide-spreading conversations and research about more than just what I know.

I’m also interested in teaching at the college level as a career, so this is not only necessary but my particular program also provides a lot of training and experience which is fantastic. I’ve done teacher training with three different classes, I’m currently teaching intro to film photography, and next semester will be intro to digital.

You’ve curated your own work for solo exhibitions as well as group exhibitions. I’m always interested in this process of self-curation and how it could influence the relationship with your work. How do you approach curation, and how does it impact how you look at your own art?

I just love exhibiting, showing my work, seeing how people respond to it, so if I can’t find exhibits then I make them! You’d be surprised at how open spaces are for a showing when you can pitch them an entire exhibition in a bow. I’ve also been fortunate enough to be offered shows to curate of other artists and that’s equally as fun, but in a different way because I don’t have work in the show.

I’ve always liked the idea that once you show work in public, it no longer belongs to the artist; you have relinquished control and ownership. So when I’m showing work with other artists, the individual artworks are no longer about me, or even about themselves, but about the relations between all the works. Everything takes on whole new meanings.

Thank you so much for your time, and for this first interview of 2026. Looking back at 2025, were there any artists or works that were particularly inspiring to you?

I’m always looking at artists that don’t seem themselves working in one medium or another. In particular, artists that are photo-based but use photography in sculptural or performative ways. Right now I’m really obsessed with Noemie Goudal, Katja Novitskova, and Mathew Brandt.

More Jeremy Starn:

Interview with CanvasRebel

Interview with Boooooom

Interview with Dovetail

Point Pleasant Publishing

Website