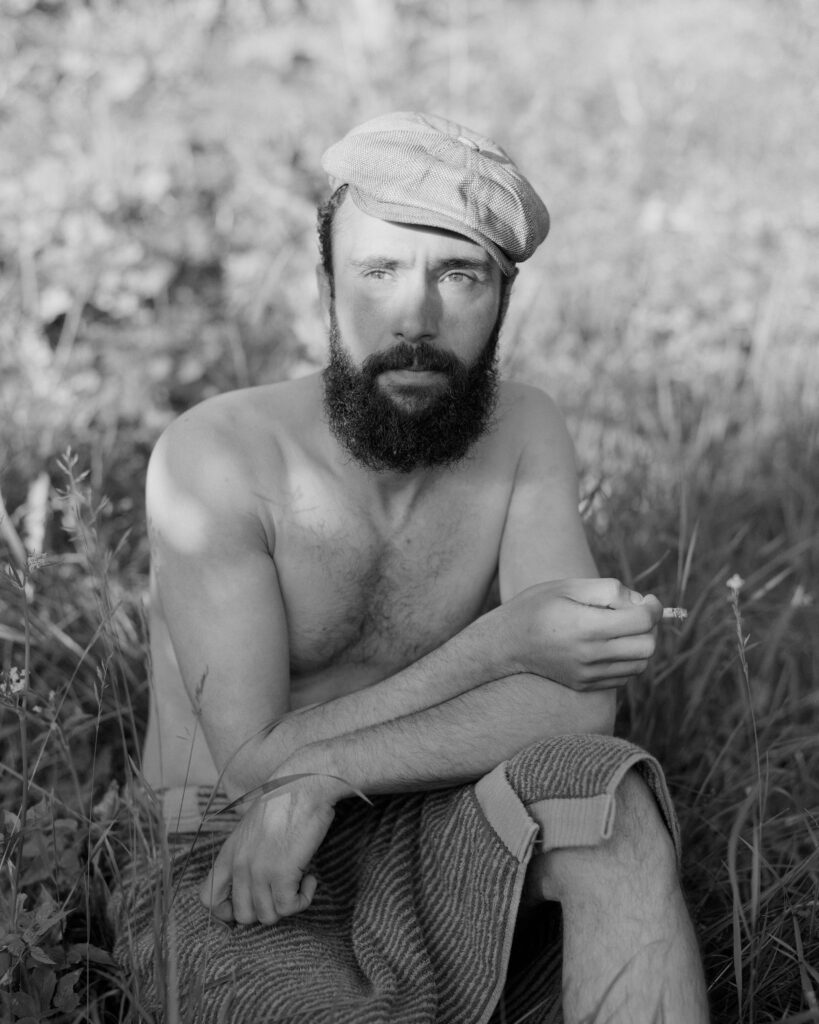

Daniel Court is a Finland-based documentary photographer whose ongoing series ‘By The Water’s Edge’ will be exhibited at Galleria Rajatila in Tampere, Finland. The series documents Finnish culture’s connection to nature, particularly through wild swimming. The portraits capture an intimacy that’s quiet and calm, like sharing a comfortable moment of silence.

I discovered Court’s work through his beautifully named series ‘The Place of No Crows’, about rural communities and depopulation in Bulgaria. Something about concepts like depopulation and disappearing communities really speaks to me, I haven’t quite figured out why. The more I look at these photos, the more the words ‘life goes on’ stick with me; even as life disappears, it somehow stays. The photos carry a sense of melancholy, but also tenderness and determination.

‘By The Water’s Edge’ will be the focus of an exhibition, and you’ll also be producing a book from the series. How has it been to go through all the photos you shot for this project over the last years? Were there any photos that surprised you, or any darlings that you sadly had to kill?

The project is still very much ongoing. I’m not sure when it will be finished – as long as I’m enjoying the process and feel there’s more to explore, I’ll keep going. It came to be in a very organic way. After moving to Finland, I quickly became drawn to how much time people spend outdoors – swimming, saunas, and being immersed in nature. I began swimming regularly myself and started photographing my friends and partner swimming. Eventually, I realized there might be a larger body of work there and began approaching it more deliberately, planning shoots and thinking more about what kind of structure it could take.

I’ve been photographing the portraits over two years now, and I tend to edit as I go, so there hasn’t been one defining moment where I’ve sat down and reviewed everything at once. The idea of a “book” is perhaps a bit misleading – it’s more of a zine or a handmade artist book, something modest that offers an insight into the project at this stage. I like the idea of making several smaller, tactile booklets while the project continues to evolve. Unfortunately, I didn’t get the funding I was hoping for this spring, so printing anything is currently on hold while I reconsider the financing.

In terms of surprises, the main one is probably just how hard I find it to be content with what I’ve made. I often feel the need to return and do better, to capture something else I haven’t quite got yet. It’s less about cutting ‘darlings’ and more about never quite feeling I’ve arrived at the image I want.

For me, the photos being in black-and-white gave the images a sense of melancholy. What made you decide to shoot in black-and-white rather than color?

I’ve always been drawn to black and white. For a long time, I pushed myself to work in color, thinking it was what I should do, but it never quite clicked with me. However, for this project, black and white just felt right. It conveys a certain calmness and stillness that mirrors how I experience swimming in Finland.

I also continue to shoot on film, which I feel contributes to that mood, but it’s also a personal thing, about the experience of photography. It’s a way to step away from screens and the digital world. Keeping the process analog helps maintain that sense of slowness and presence.

You moved to Finland in 2016, and your projects ‘By The Water’s Edge’ and ‘In These Landscapes, The Eye Can Rest’ both document the country and its culture. What role has photography played in adapting to Finnish culture?

Photography has been central to how I’ve processed and understood my life here. ‘In These Landscapes’ was an early attempt to engage with Finland through the countryside and the phenomenon of rural depopulation. But in the end, I felt too much like an outsider. The language barrier was difficult, and I found it hard to explain my intentions. I think I was even questioning them myself. In the end, the project hit a wall and has only been exhibited once.

In contrast, ‘By The Water’s Edge’ developed very naturally from my lived experience. Swimming became a huge part of my life in Finland – it helped me adapt and find a community. So this project is really a personal reflection on my experience, not just a documentary. It grew from photographing my own circle and gradually expanded outward, but it always felt rooted in something genuine.

Your project ‘The Place of No Crows’ focuses on the disappearing rural communities of Bulgaria. I love the layeredness of the project, and I love the name. What does the name mean, and why did it stick with you?

Thanks! I’m also quite fond of this name. I was traveling through Bulgaria with a translator, looking for one particular village. We stopped to ask an old man for directions, and he pointed down the road and said something in Bulgarian that my guide translated, roughly, as “the place of no crows” or “the place where no crows go.” My guide wasn’t familiar with the phrase – it wasn’t something idiomatic that he recognized or had heard before – but we interpreted it as meaning that the place was so empty, not even the crows would go there.

It immediately struck a chord with me. It encapsulated the desolation of these places in a poetic, slightly surreal way. I immediately knew it would be the title.

When documenting areas such as rural Bulgaria, where people might not speak much English, do you have any specific tactics for engaging with the locals?

I found people in Bulgaria to be incredibly welcoming. I can’t recall anyone being hostile or refusing to be photographed. Often, people went out of their way to help me. One man, for instance, spent a whole day trying to get me access to the local school during the holidays – he had his entire family involved, running around trying to find the right key.

There was a real generosity and curiosity about what I was doing, even when people spoke with melancholy or nostalgia about their lives. I think having a translator helped, of course, but people were usually willing to engage with or without a full understanding of what I was doing. They saw that I was taking an interest in something they felt was important and that was enough.

On the topic of names again: in earlier articles, ‘By The Water’s Edge’ was referred to as ‘Watersong’. What prompted the name change? And in general, how do you approach naming your projects?

I always struggle with project names, but they can really help focus the direction of a project, so I need them to feel like they belong. Often, I begin with a placeholder, something that feels close enough but eventually changes as the project develops.

Naming this project has been especially difficult. ‘Watersong’ came from Waterlog by Roger Deakin, a book I read years ago about wild swimming in the UK. That book made a big impression on me, and the word ‘Watersong’ surfaced somehow from that. But it never felt completely right – it was too lyrical or poetic, maybe, and didn’t say or imply anything meaningful.

The title ‘By The Water’s Edge’ finally came from the last few words of a sentence in another book – I think it was Silent Spring by Rachel Carson, though I can’t say for certain now. When I read the words, it just clicked – it had that slightly idiomatic feeling, like ‘The Place of No Crows’. It also has a quietness to it that mirrors the work itself.

After obtaining your Bachelor’s degree in 2012, you worked for a number of cultural institutions, including Getty Images Gallery in London and Helsinki Art Museum. Did working for these organisations have any influence on your artistic practice?

Absolutely – working at Getty Images Gallery was a huge part of my education. I was enthusiastic about photography when I started, but I couldn’t say that I had a deep background or understanding in photography. The gallery worked closely with the Hulton Archive, which includes an extraordinary range of 20th-century British press photography – from Picture Post and The Daily Express archives to Herbert Ponting’s images from the British Antarctic Expedition of 1910-1913. I was constantly exposed to an incredible range of work.

There was also an in-house darkroom, and I learned so much from the printers – how to handle negatives, how to judge tones, how to really look at an image. It gave me a deep appreciation for the craft of film photography. I also got to meet and assist many fantastic photographers – Michael Putland for one, he taught me a lot about portraiture and the importance of communication, of putting people at ease in front of the camera. Looking back, I am sure that experience influenced how I approach my own work today.

More Daniel Court:

Interview about ‘By The Water’s Edge’

Booooooom article about ‘The Place of No Crows’

Website