Adeline Care is a photographer and director who divides her time between Paris and the hills and trees of the Dordogne. Throughout her projects, Care captures landscapes with such detail, vividness and tactility that deeper meanings and histories start revealing themselves. They aren’t passive environments for us to inhabit, they are rich characters that live and breathe with or without us.

But it’s not just landscapes; there’s also her gorgeous Technicolor-like experiments and her beautiful portraits, all capturing something intangible in their own way. So much to discover, and so much to be revealed.

Thank you so much for discussing your work with me! Looking at projects like ‘Mineral Cloud’, ‘Minas Sangre’ and ‘Aithô, Je Brûle’, I love how tangible every image feels, with so much eye for the character and texture of the landscape. How did you learn to look at a landscape this way?

I grew up in a small town surrounded by forests and rivers. When I started photography as a teenager, I would often wander alone with my first camera, completely mesmerized by nature – it always felt like a presence, almost like a character in itself. Over time, I became more and more drawn to mineral and vegetal textures. I want viewers to almost feel the surface of the landscape through my images.

On your Instagram, you described ‘Minas Sangre’ as “landscape trauma”. Where were these photos taken, and what is the meaning of landscape trauma?

The subtitle “landscape trauma” was inspired by one of the final scenes of Memoria by Apichatpong Weerasethakul. There’s a deeply moving moment where the character listens to the land and hears it resonating with the memory of past events, like the earth itself is holding pain, echoing with invisible wounds.

While traveling in the south of Spain, I came across vast, open wounds in the land, huge mining scars, unnatural red rivers, and hollowed-out hills. It immediately brought me back to that scene in the film. I saw how the soil there, too, seemed to be suffering. It was a place shaped by human machines, industry, extraction, and yet, somehow, nature was growing back through it all. It felt both tragic and resilient. That’s what I meant by “landscape trauma”: land that holds the memory, like a living body.

There’s something hopeful about seeing your work about disappearance next to your portraits of the Paris Saint-Germain Under-19 women’s team. This project seems very different from your other works. How did this collaboration come about, and how did you approach these photos?

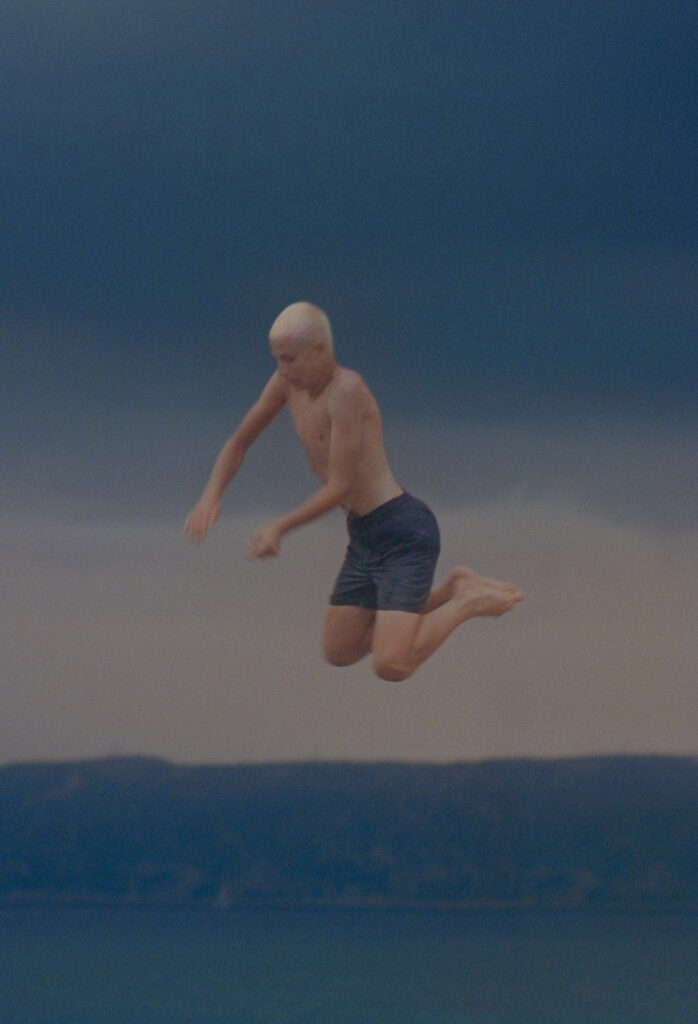

This collaboration came through Studio Artera, an artist agency I work with that often partners with brands. Since it was a “carte blanche” project, I knew right away I wanted to photograph the PSG U19 women’s team. I was interested in capturing both their strength and their bond, the multiple layers of their identities as young athletes. Originally, I had planned for warm light and sunset tones, but the cloudy weather unexpectedly enhanced the mood of the portraits.

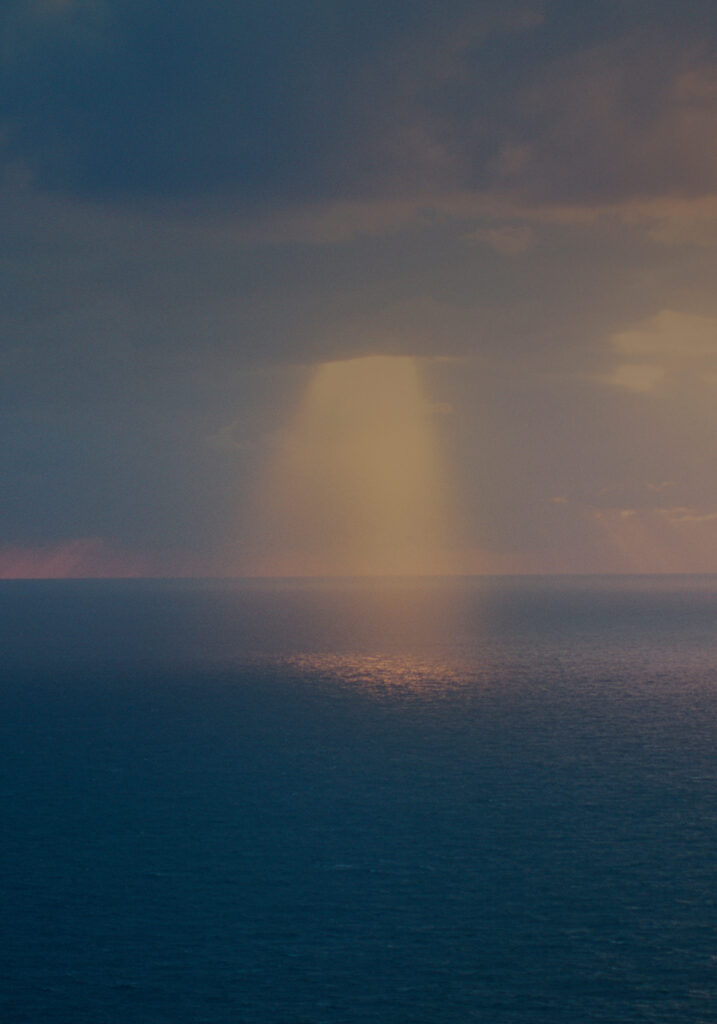

‘Marseille, Tempête!’ captures scenes of seaside fun right before a storm. What drew you to the city of Marseille? And in general, how do you decide on photographing a certain place?

One of my favorite aspects of photography is location-scouting. Sometimes it’s pure luck, but often I spend hours online researching unusual landscapes or natural phenomena, building lists of places I want to visit, mostly in France or nearby countries. When I get there, I walk a lot to discover different vantage points. I like to map places visually, creating a kind of poetic cartography that reveals their magical realism.

Marseille has always been one of those cities that keeps calling me back. Its raw energy and the contrast between sea and concrete make it so visually rich and unpredictable. This series actually began quite spontaneously: I happened to be on the seafront just minutes before a major storm rolled in, and the colors and light were surreal. When I developed the film, I knew I wanted to continue exploring Marseille during stormy weather, chasing that mix of urgency and grace I felt that day. It’s still an ongoing series, and I now regularly check the weather to return when storms are coming.

The project ‘Liquid Time’ seems more experimental in its use of color and contrast. What was the motivation behind this project, and what does the name ‘Liquid Time’ mean to you?

‘Liquid Time’ emerged during the lockdown. I was fortunate to be confined in a place close to nature with friends, and like many of us, I felt time become strangely elastic. It was a rare moment to slow down and experiment more freely. My friend Laurie helped me reflect on this idea of time as something fluid, malleable. This series became a turning point for me, giving me space to work more with light, to explore portraiture in new ways, and to embrace experimentation.

In an interview with the GOBELINS Alumni platform, you tell people not to hesitate to make mistakes, because that’s when you learn the most. Could you tell more about a particular mistake that you remember learning a lot from?

I learn something after almost every shoot, whether from mistakes or simply from realizing what I could improve. That might be lighting, composition, direction, or simply making people feel comfortable in front of the camera, which can be a vulnerable experience for many.

As for a specific mistake, since we were talking about ‘Liquid Time’ and experimentation: I was photographing Laurie behind a fire that had just gone out. In my rush to change the film roll, I accidentally opened the camera before the film had fully rewound. I was really upset, thinking the images were ruined. But when I developed them, I discovered that some frames had been burned right over the fire, creating ghostly overlays I could never have planned. It taught me to slow down, and reminded me that mistakes can sometimes lead to unexpected magic.

In that same interview, you name the films by Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Werner Herzog as big inspirations. What about their work inspires you so much?

Apichatpong Weerasethakul inspires me deeply in the way he crafts stories and dreamlike narratives with very minimal means. With Werner Herzog, what strikes me most is how nature is never just a backdrop in his films; it’s a force of its own. There’s a sense that the jungle, the volcano, the landscape itself can devour everything in its path. I’m also deeply inspired by the photographer Graciela Iturbide and the strength of her portraits. I was lucky to see an exhibition of her powerful analog prints, they’ve stayed etched in my mind ever since.

More Adeline Care: