It can be hard to engage with architecture and spatial design, especially as a layman, beyond simple descriptors such as nice/ugly, practical/impractical or spacious/cramped. Our built environment contains and produces all these meanings and hierarchies, and I feel like I don’t have the required understanding to uncover them, which only makes architecture more mysterious and fascinating to me. This is why I love works that help me see these seemingly invisible elements, either by addressing them directly, or by discussing them through metaphor or abstraction.

The work of millonaliu can appear inaccessible – it’s definitely theoretical and layered and complex – but at its essence is the very clear goal of finding ways to understand the spaces we inhabit. How are they formed? Who forms them? And why? The Rotterdam-based artist duo, consisting of Klodiana Millona and Yuan Chun Liu, playfully investigates and challenges our ideas of space. They help us engage with the many geographies of our world, showing how even a grain of rice can contain layers of power.

If I’m correct, you met studying Interior Architecture at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague. What made you decide to start working together as millonaliu?

We did meet during our master’s studies at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague. But perhaps more importantly, we met in the spaces that extend beyond its curriculum – those shaped by our shared experiences as migrants studying abroad, at the very center of Europe, and, by extension, within the very place that so effectively architectures its many peripheries – the places we came to understand ourselves as coming from.

These experiences are, in themselves, very spatial. They’re produced by specific architectures, but they also shape the way you move – or are made to move – through space. In many ways, we met again within the vacuums that such experiences and spatial conditions revealed inside the structure of that education.

Our collaboration emerged from that recognition: that so much of architectural education, and design practice more broadly, leaves certain stories, identities, and spatial realities unacknowledged. And even when they do, it’s often through a kind of flattening, exoticizing gaze. Working together became a way to understand that, to question it, and to try to fill some of those gaps. Millonaliu was born not just from shared interests, but from a shared need to question where and how knowledge is produced – and to find ways of navigating together the architectures of citizenship that are imposed on us.

You seemingly have very different cultural backgrounds, with Klodiana being from Albania and Yuan Chun from Taiwan. I was wondering what you’ve found in common between these different cultures.

The scorching sun, the fatal love for food, and the ability to reinvent everything else around these two! (joking)

Both Albania and Taiwan inhabit realities that are shaped in relation to larger geopolitical forces, both carry histories of radical transitions and negotiation, and both experience a kind of peripheral positioning in relation to the so-called centers. There’s also similarity in resilience, an ability to adapt and reimagine within systems that don’t see you. That practice – of making space where there was none – connects us deeply and has shaped how we think and how we work.

Architecture is something I find really interesting, but that also feels very closed off without a background or formal education in this discipline. How can people like me, who don’t have this formal knowledge, still analyze and engage with architecture in a critical way?

Architecture is more than its codes, drawings, and technical language. In reality, it’s something everyone experiences every day. Architecture is everything and everywhere. As the writer Georges Perec beautifully traces through his writings, space unfolds from the blank page of a notebook to the space of the bed, the bedroom, the apartment, the neighborhood, the city, the country, the continent, and the world.

You don’t need a degree to perceive how a space makes you feel – whether it includes or excludes, how it directs movement, how it transforms the city, how it makes your neighborhood less affordable, how it marks class difference, how it takes away someone’s livelihood, how it erases, how it encloses, how it isolates certain bodies, and so on.

To engage critically with architecture is, first of all, to understand that it never takes place in a vacuum. It is about contextualizing where it takes ground and how it spatially implements larger political projects. A wall, for example, marks two spaces – but who stands on which side is not dictated by architecture; it’s political. Architecture itself does not invent these differences, yet it is through architecture that such political projects of difference are fully realized.

So, to engage is to observe; to ask: Who is this space made for? What histories does it carry? What forms of movement or behavior does it allow, or control? Those questions are already a form of spatial reading.

You’ve both lived in the Netherlands for about 10 years. How would you define Dutch architecture and its built environment, and what do you think it says about the Netherlands?

The Netherlands is actually a fascinating place to think about architecture because the built environment here is never that accidental. There’s a strong belief in order and in planning. Even the landscape itself – the polders, the dikes – is an architectural project. The Dutch built environment reflects a deep trust in design as a tool for managing life, and with that, also a deep anxiety about what lies outside control.

At the same time, what interests us are also in looking at the rich traditions in resistance, the strong spatial practices challenging this super order, and structures of life commodification – the long tradition of squatting, networks of solidarity in that very community and the legacies they have nowadays in the built environment.

The squatting movement paved the way for the repurposing of architecture, such as schools, hospitals etc reimagined into collective homes and cultural venues, giving rise to new forms of living and working together. The combined home-workspace arrangement, for instance, proliferated within squats long before it was adopted as an official housing typology.

For us, these histories of resistance are equally architectural. They show that space is never fixed – it’s negotiated, occupied, reclaimed. They remind us that architecture is not only about control, but also about the capacity to imagine and build otherwise.

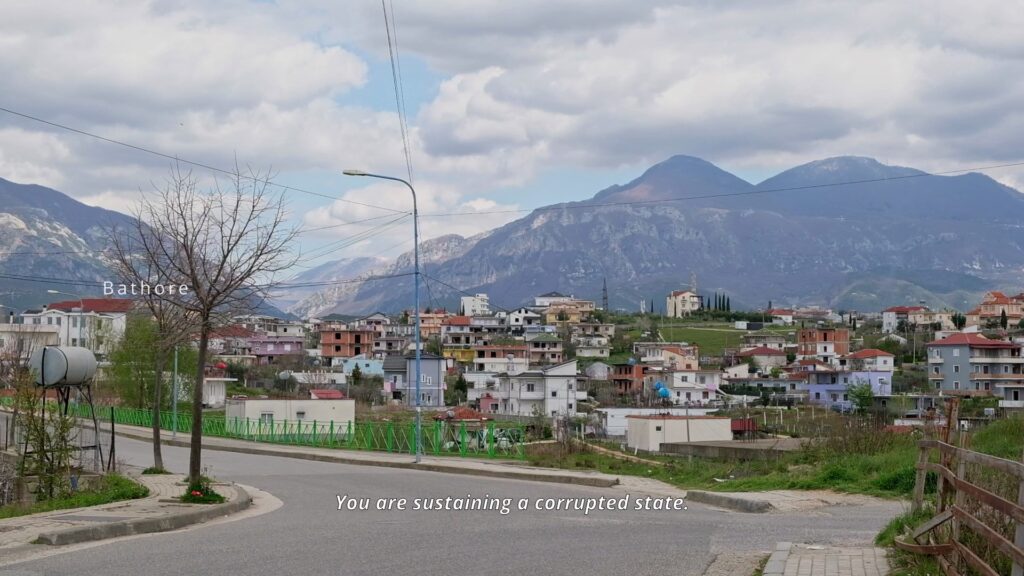

Your short documentary The City That Was Not Supposed To Be On The Map deals with the Albanian municipality Kamza. Could you tell me more about Kamza? What drew you to this place?

The documentary is produced collectively, with the local activist collective ATA (meaning ‘them’ in Albanian) and other contributors, as a result of ethnographic fieldwork and engaged filmmaking.

Kamza is a self-made neighborhood turned city in Albania, created incrementally after the 90s, mainly due to internal migration that followed the transition from one of the most isolated socialist dictatorships. Migrants, mainly from the mountainous northern and northeastern regions – areas long excluded from state development policies, both before and after the dictatorship – settled in Kamza in the first years after the regime’s collapse, in unprecedented numbers.

Its first neighborhood, Bathore, was built entirely through self-help housing and it is characterized by whole-family migration. Migration happened within an institutional and legal vacuum; although the first migrants arrived in 1991, infrastructure planning did not begin until 1997. People developed their own survival strategies to navigate precarious conditions and ongoing land conflicts with the state and private owners. Bathore comprises the largest self-built area in the whole country. It came to exemplify all (what are considered but continuously challenged by activists, local communities and researchers) “informal”, “illegal” and unplanned developments that occurred in Albania after the 1990s, and nowadays it is used as a derogatory term among both the (self-titled) left and right wing politicians in public debates.

For me (Klodiana) Kamza is a spatial school in itself that builds at the intersection of law(less) and space, the production of geographies of (in)justice and resistance. Against the epistemic frameworks of mapping, territory, and boundary that position its inhabitants as “outside” the law, we instead read Kamza through this film as a radical geography of spatial justice – one articulated through the most fundamental act of existing and resisting: the migrant household’s practice of home-making.

Through architecture and spatial design, your work deals with a variety of topics including national identity, immigration, citizenship and place. Going through all your projects, I found myself wondering: how has your work influenced your experience of ‘home’?

In a way, most of our work begins with the question of home. All the topics you mention are not in spite of it, but because of it – how they continually shape and unsettle our idea of what home can be.

Since the notion of home as a fixed place is not able to host our own conditions of belonging, we’ve come to understand home more as a practice – as an ongoing act of making. Home-making as space-making – one that often stretches across different geographies and temporalities. Sometimes contained within the scale of the body itself and at others spread across continents.

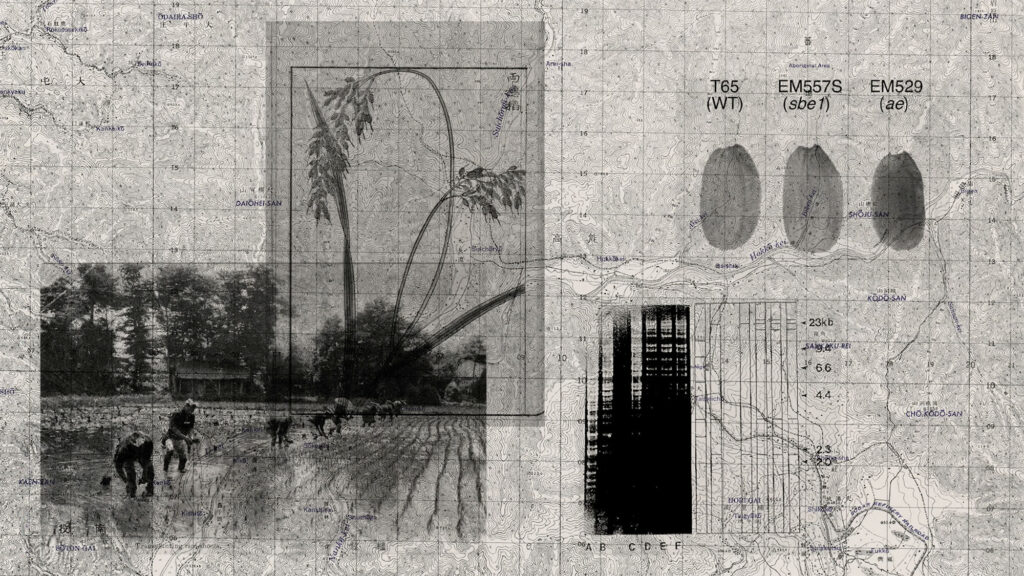

On your website, you categorize a number of your projects as ‘Critical Cartography’. What interests you so much about cartography, and what is the power of alternative cartographies or counter-mapping?

Cartography is inherently an instrument of power. Maps as much as they represent a territory, they produce that territory. In our work we think through the practice of counter-mapping to interrogate constructions of history, colonial narratives and architecture’s implication in perpetuating a regime of invisibility. What is omitted from maps? What is rendered invisible? Who or what dictates these absences? Experimenting across moving image, sound, text, installations, and publications, we think of all our works as maps that resist linear storytelling, and instead trace and record fragmented histories.

Although it took me a bit to understand the aspect of quantum mechanics, I immediately found collaborative project Wave Function Collapse fascinating. How did you approach your collaborators for this project, and what did the curation process look like?

Wave Function Collapse captured the frustration with the regime of the visual, made ever more present during the COVID-19 lockdown, when it reached its peak. Home turned into the most overexposed image circulating across screens – a space constantly watched, aestheticized, and idealized. For those who had one, it became both a shelter and a site of confinement. Everyday life was compressed into the domestic interior – work, rest, care, education – everything folded into a single image of containment. Yet behind these images lay exhaustion, anxiety, and isolation.

It became clear how the domestic was also functioning as an instrument of control – an architecture of isolation and discipline. This is exemplified in the work by Diana Malaj and the collective ATA, which documents how, under the pretext of safety and the ban on public gatherings, residents of Zall-Gjocaj National Park were excluded from court hearings about the construction of two dams in their village. Although their bodies were confined at home, the machines of destruction continued to operate. In this work, the activists confront the judge’s lone recorded voice – proclaiming justice in the name of law – with the missing voices of those whose lives that law should have protected.

The project began as an opposition to this fixed gaze, to this visual saturation, asking whether we could move from excessive looking toward listening – using the aural as a form of inquiry. Each work within Wave Function Collapse approaches sound as a way to produce knowledge differently – to trace the invisible, the unheard, the marginal. Listening becomes the main form of engagement, a way to tune into the world beyond the dominance of the image. Some collaborators work primarily with sound, most do not, yet together the works form a kind of sonic remapping of that moment. We were less interested in the sound itself, and more on the practice of listening.

Through Bandcamp, you can buy Wave Function Collapse as an aural publication comprising a cassette tape and an artist book. I find the cassette tape to be oddly fitting, though I’m not sure why. Why did you choose to release it on cassette?

Since the beginning, we were interested in experimenting with the idea of an aural publication – something that could exist outside the dominant infrastructures of image and screen. During the process, we talked a lot about algorithms, surveillance, data extractivism and the corporate platforms that became hyper-used during the pandemic. We began to ask how our work could circulate differently – how to evade, or at least resist, these systems of control. That’s how we arrived at the cassette tape: a slower, more tactile medium that escapes digital immediacy and allows for a different kind of listening.

In a way, choosing the cassette was also a spatial gesture – a small act of engaged listening, of finding another route for circulation, one that resists capture and insists on a physical presence through sound.

More millonaliu: